After Having His Motel Seized by the Government, Victim of Civil Asset Forfeiture Reflects on His Fight

Russ Caswell, owner of Motel Caswell in Tewksbury, Mass., fought the law and won. Now, he’s reflecting on his experiences with a law enforcement tool known as civil asset forfeiture as policymakers in Washington, D.C., and across states from coast to coast, debate the practice.

“The government tried to take [Motel Caswell] based on just a handful of drug activity cases that they had that I didn’t even know had existed,” Caswell told The Daily Signal.

Caswell’s father built Motel Caswell in 1955, and in the 1980s, he and his wife, Patricia, took over managing the business. The motel, which they owned mortgage-free, was supposed to provide the Caswell’s with their retirement.

However, several years ago, the Drug Enforcement Agency and Tewksbury Police Department seized the property because guests at the motel had been arrested for drug crimes.

Caswell was unaware of the illegal activity, which took place behind locked doors, but he had always cooperated with law enforcement in the past.

The state and federal agencies argued that because there had been drug arrests on 30 different occasions, the property was theirs for the taking. The Caswells, though, had rented rooms in the motel more than 125,000 times over a period of 17 years.

Though the federal government and local police department contended they had seized the property because of the crimes committed there, Caswell believes they wanted to sell Motel Caswell for a profit.

And when Caswell filed a lawsuit challenging the seizure, a DEA agent confirmed his suspicions.

During depositions, Special Agent Vincent Kelly told lawyers that he was tasked with finding properties to be forfeited. Often times, he said, the agency wouldn’t go after a property unless an owner had more than $50,000 worth of equity.

Motel Caswell was worth $2 million.

>>> How California Cities Are Making Millions Seizing Property and Money From Law-Abiding Citizens

“That’s what they were after,” Caswell said. “This had nothing to do with drugs. It was just an excuse to steal property from us.”

With the help of lawyers from the nonprofit Institute for Justice, which represented him pro bono, Caswell was successful in getting his motel back. However, the government did try to convince him into settling, which Caswell called “nothing more than an extortion plot.”

“They had nothing to get us on because we did nothing,” he said of law enforcement.

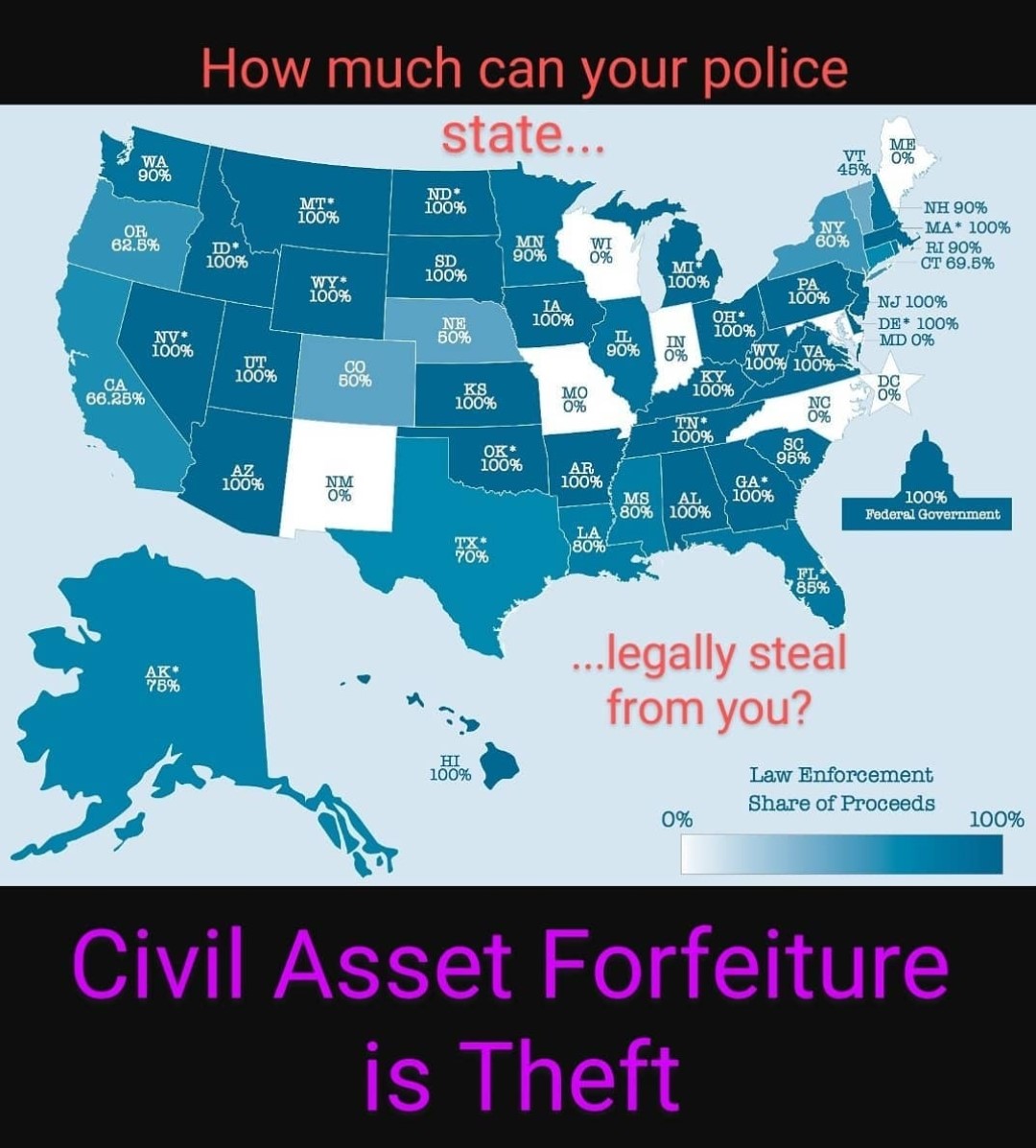

Civil asset forfeiture is a tool that gives law enforcement the power to seize property if it’s suspected of being related to a crime. The practice began decades ago with the intention of curbing money laundering and drug trafficking, but law enforcement officials have been using civil asset forfeiture to seize property and money for profit.

In fact, law enforcement agencies have made more than 55,000 seizures of cash and property worth $3 billion since 2008 through a program known as Equitable Sharing, which allows local law enforcement agencies to share in the proceeds from seizures.

Often times, people who have their property seized have no idea they committed a crime, like Caswell. The practice, according to policy experts calling for reforms, turns the principle of “innocent until proven guilty” on its head.

Advocates of civil asset forfeiture reform believe the practice hurts innocent property owners refuting their forfeitures. Additionally, many argue the tool creates perverse incentives for law enforcement, as the proceeds from seized cash and property often benefit police department and prosecutors’ offices.

Caswell was ultimately successful in fighting federal and local law enforcement for his property, but many victims choose to settle rather than undergo years of litigation and surrender portions of their cash and property. Still, he has a hard time reconciling why it was the presence of drugs in Motel Caswell that caused law enforcement to act.

“If you think about it a little bit, they let the drugs come into town—probably coming in from Mexico at lot of it. It comes all the way across the country through a whole bunch of states. Nobody catches it. It gets into Massachusetts and nobody catches it. Then it gets onto my property and all of a sudden it’s my fault,” Caswell said. “And they want to steal my property and reward themselves for their own failure. They’re the ones who should be keeping drugs out of Massachusetts and the country, not some motel owner. That’s up to them.”

![PrivateProperty3-1250×650[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/PrivateProperty3-1250x6501-1.jpg)

![image-4[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/image-41.png)

![CF-5-1000×556[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/CF-5-1000x5561-1.png)