America’s Asset-Forfeiture Scam Is Law Enforcement’s Disgrace

If Congress won’t act, the Supreme Court may move to rein in the practice.

One day, the federal government just might sue my truck. I’ve got a Toyota Tundra. It’s big, it carries lots of stuff, and it’s extremely useful for moving furniture, hauling trash, and driving off-road. Consequently — and this is something every truck owner learns — it’s in demand. I’d say once every two weeks someone asks to borrow it. A neighbor is giving lawn furniture to their grandma. The church wants to use it for a work day while I’m out of town. A friend is throwing away a trampoline. I lend it out freely, and I don’t always know who’s riding in my truck.

Depending on who’s driving, who’s riding, and where they go, I could one day wake up to find that my truck is gone — in the hands of the government — and I’ve got an expensive uphill climb to get it back. Moreover, my truck can disappear into the maw of the bureaucratic state without a single person being charged with or convicted of a crime.

The process is called “civil asset forfeiture,” and here’s how it works. To borrow from real-life fact patterns from other cases, imagine that you’re driving through an unfamiliar town in my borrowed truck. You’ve got out-of-state license plates, you’re a little bit lost and confused, and you’re carrying an unusual amount of cash. You’re driving to pick up a couch you’ve purchased on Craigslist, but you think you put the wrong address in your phone.

The neighborhood is a little seedy, you’re driving slowly, and soon you see the blue lights behind you. According to the sheriff’s deputy, you’ve been driving “suspiciously” in a “known open-air drug market.” The deputy conducts a search and finds your cash. He’s unimpressed with your explanation, and within a few minutes, a police dog “alerts” that there are trace amounts of cocaine on your money. You’re incredulous. You’ve never even seen cocaine much less snorted it or paid for it. You have no idea that large amounts of currency in common circulation contain traces of coke.

The officer next informs you that he’s got “probable cause” to believe that both the cash and the truck were being used for the purchase and transportation of drugs, and he’s seizing both. Come to think of it, he realizes that you probably used your cell phone to set up the alleged transaction, so he’s going to take that also. He lets you make a call to get a cab, and he gives you a few extra minutes to call me, to tell me that your cash and my beautiful full-size pickup are now in the hands of first the Smith County Sheriff’s office and then the federal Drug Enforcement Agency.

TOP STORIES

Nikki Haley’s Sin Isn’t Racism

The Hard Realities Facing Ron DeSantis

Maine Secretary of State Rules Trump Is Disqualified from 2024 Ballot

Francis Collins’s Covid Confession

A Reckoning for the Rising-Inequality Narrative

The Peace Processors Return

No problem, right? This is just an inconvenience, right? Neither of us did anything wrong, we committed no crimes, and there is no way that the prosecutor can possibly prove criminality beyond a reasonable doubt. In fact, neither my friend nor I is ever charged.

What happens next, however, is beyond strange. The government sues my truck, and in the case of United States vs. Cool, Slate-Gray Toyota Tundra, it only has to prove by a “preponderance of the evidence” that it was used in the commission of a criminal act. Oh, and did I mention that if the government can “prove” that my truck was used unlawfully, then the sheriff’s department (or whatever agency took the vehicle) can sell it and use the proceeds to pad its department’s budget?

That is civil asset forfeiture. It’s a gigantic law-enforcement scam (in 2014 the government took more money from citizens than burglars stole from crime victims), and it’s a constitutional atrocity. It’s a constitutional atrocity that Donald Trump’s Department of Justice just expanded. Yesterday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions revived an abusive program that allows state authorities to seize property and then transfer the property to the federal government to implement the forfeiture process. Once the Feds obtain forfeiture, they then share the proceeds with the seizing state agency. This allows state law enforcement to explicitly circumvent state forfeiture restrictions and profit while doing so.

Even worse, Sessions’s announcement of the change was misleading. In a speech to the National District Attorneys Association, he said that “no criminal should be allowed to keep the proceeds of their crime.” Most Americans would agree with that statement. I agree with that statement. But civil forfeiture allows the government to deprive citizens of their property even when it doesn’t even try to prove that the citizen committed a crime.

Examples are endless, but one of the most notorious is the case of Bennis v. Michigan. In 1996, a conservative majority of the Supreme Court affirmed the seizure of a wife’s car when her husband used it while soliciting a prostitute. Thus, she suffered a double betrayal — at the hands of a faithless husband and an overreaching state.

The Supreme Court has traditionally affirmed expansive civil forfeiture rules by reference to colonial practices rooted in admiralty, piracy, and customs law. Back when ship owners were often a continent (and a dangerous ocean voyage) removed from their property, the government seized ships and cargo in lieu of bringing charges against the owner himself. From that limited, modest launching pad, SCOTUS has empowered an avalanche of abuse.

There are signs, however, that the Court may be running out of patience. In a stinging concurrence with denial of certiorari in a recent forfeiture case, Justice Clarence Thomas openly questioned whether “modern civil-forfeiture statutes can be squared with the Due Process Clause and our Nation’s History.” As Thomas notes, the abuses can be horrifying:

This system — where police can seize property with limited judicial oversight and retain it for their own use — has led to egregious and well-chronicled abuses. According to one nationally publicized report, for example, police in the town of Tenaha, Texas, regularly seized the property of out-of-town drivers passing through and collaborated with the district attorney to coerce them into signing waivers of their property rights. In one case, local officials threatened to file unsubstantiated felony charges against a Latino driver and his girlfriend and to place their children in foster care unless they signed a waiver. In another, they seized a black plant worker’s car and all his property (including cash he planned to use for dental work), jailed him for a night, forced him to sign away his property, and then released him on the side of the road without a phone or money. He was forced to walk to a Wal-Mart, where he borrowed a stranger’s phone to call his mother, who had to rent a car to pick him up. [Citations omitted.]

More from

DAVID FRENCH

America’s Racial Progress

Inside the Rise and Fall of ISIS’s Caliphate

When Cops Create Their Own Risk, Innocent People Die for Their Mistakes

Thomas rightly argues that a narrow colonial-era practice based on concerns that the potentially guilty person was beyond the jurisdiction of the United States is hardly justification for a sweeping forfeiture regime that permits prosecutors to take billions of dollars in property from Americans without actually proving criminal misconduct. Given Justice Neil Gorsuch’s well-known skepticism of expansive executive powers and respect for originalism, properly understood, it is probable that Thomas has at least one other ally on the court, possibly more. It would be delightful indeed to watch Trump’s SCOTUS pick help rein in Trump’s DOJ.

But if the last 30 years of constitutional jurisprudence have taught us anything, it’s that we can’t count on courts to protect the Constitution when the War on Drugs is at issue. Forfeiture expanded dramatically as part of the War on Drugs, and the Supreme Court has proven that it will undermine even the First Amendment when constitutional rights clash with drug-enforcement priorities. As our editors argue today, it’s time for Congress to act. If asset forfeiture is designed to punish crime, then prove a crime. Make it part of the criminal process, submit it to the same burdens of proof, and end the conflict of interest that incentivizes agencies to line their pockets with seized goods. No one objects to seizing a drug dealer’s cash, but prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he’s a dealer and those are his ill-gotten gains.

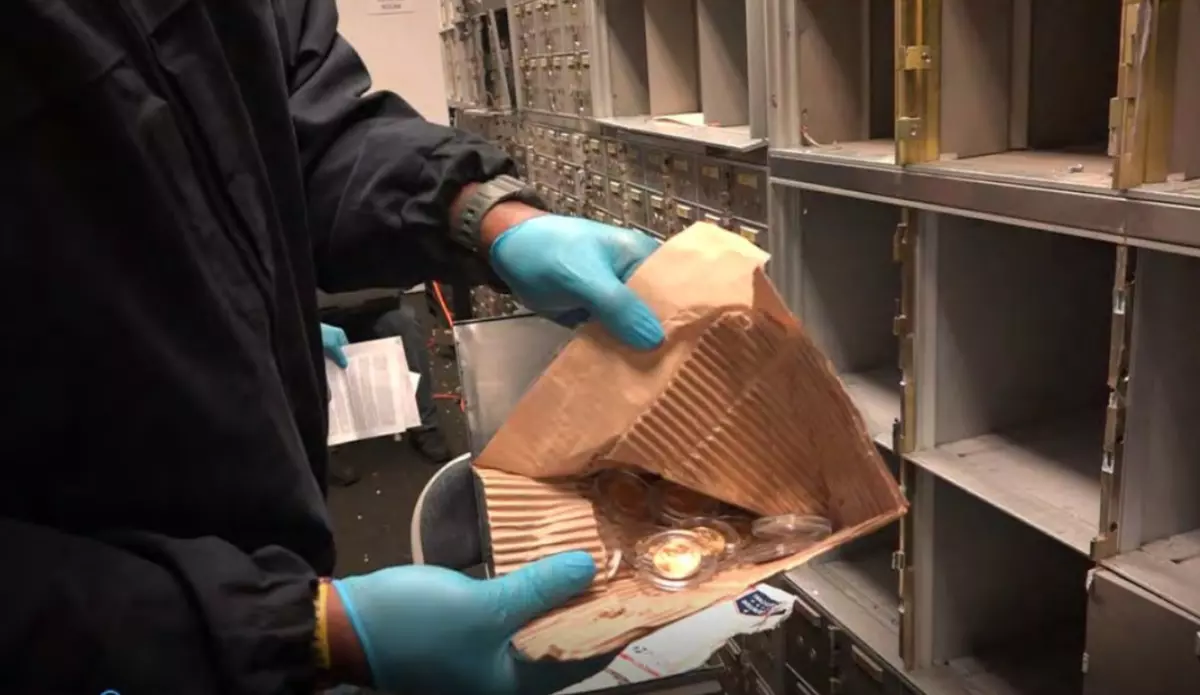

Law-enforcement agencies love to showcase their most impressive forfeiture successes, and I must admit there’s a surge of glee in seeing a crime boss lose his Lamborghini. But the daily reality of forfeiture is something else altogether. A Department of Justice inspector general report found that “almost half of the Drug Enforcement Agency’s seizures in a random sample weren’t tied to any broader law-enforcement purpose.” That’s unacceptable, it’s unconstitutional, and it’s crying out for meaningful legal reform.

![billionaires-DOJ[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/billionaires-DOJ1.jpg)

![government-cash-seize[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/government-cash-seize1.jpg)

![Font-NPR-Logo[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Font-NPR-Logo1.jpg)

![20180903_d2c5ea2e-0888-57b3-b04a-ab689f32c70c_1[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/20180903_d2c5ea2e-0888-57b3-b04a-ab689f32c70c_11.jpg)