Alabama businessman Frank Ranelli had 130 computers seized from his computer repair business based on a tip that he was dealing in stolen merchandise.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

A recent poll found that 82 percent of Americans support a conviction prerequisite, and it is easy to understand why.

Alabama law awards 100 percent of the proceeds of successful forfeitures to the agencies doing the seizing and the prosecutors handling the cases.

Nationwide, a broad, bipartisan consensus is forming that civil forfeiture laws have become too powerful, too stacked against innocent property owners.

This week I had the privilege of meeting with some of Alabama’s leading lawmakers and policy experts to discuss an issue of urgent importance: protecting the property and due process rights of Alabamians by reforming the state’s civil asset forfeiture laws.

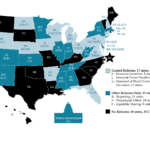

Twenty-five states and the nation’s capital city have already done so, and Alabama is poised to join them. The Forfeiture Accountability and Integrity Reform Act, or FAIR Act, introduced by Rep. Arnold Mooney and Sen. Arthur Orr, proposes to abolish the practice in the Heart of Dixie.

If passed, Alabama would be the fourth state to take this step, and the fifteenth to require a criminal conviction before the government can permanently strip a person of his cash, property, or home.

A recent poll found that 82 percent of Americans support a conviction prerequisite, and it is easy to understand why. Civil forfeiture may have been ramped up in the 1980s for a noble purpose—to relieve drug kingpins, criminal organizations, and money launderers of their ill-gotten gains—but these worst-of-the- worst offenders are no longer its principle targets.

Consider a recently-released report on forfeiture in Alabama, Forfeiting Your Rights. Analysts examining civil forfeiture cases filed in 14 Alabama counties in 2015 found that half of these cases involved amounts less than $1,372.

Kingpin money, this is not.

This gradual slide towards the seizure of small amounts of currency and property has created serious problems. First, seizures require little—and frequently no—evidence of criminality, meaning even wholly innocent people can find themselves stripped of their possessions.

Alabama businessman Frank Ranelli found this out first-hand. He had 130 computers seized from his computer repair business based on a tip that he was dealing in stolen merchandise. He proved otherwise, yet seven years later his property has yet to be returned.

Second, challenging a forfeiture action in court is exceedingly difficult. In Alabama, prosecutors need only demonstrate that property is tied to crime to a court’s “reasonable satisfaction” to prevail. Once it clears that low bar, unless the case deals with real property, the burden shifts to the owner to prove, in essence, his own innocence, and he must do so without an attorney if he cannot afford one.

That is a tall order, and perhaps explains why, according to the study, the state won nearly 80 percent of its forfeiture cases. With the deck stacked against them, and hiring a lawyer frequently costing more than the value of what was taken, many innocent owners have no realistic choice but to give up. Indeed, the report discovered that 52 percent of forfeiture cases statewide ended with default judgements—uncontested wins for the state.

Finally, Alabama law awards 100 percent of the proceeds of successful forfeitures to the agencies doing the seizing and the prosecutors handling the cases. This creates a powerful incentive to utilize civil forfeiture not as a law enforcement tool, but a source of revenue. Seventy agencies across the state netted $2.2 million from the cases they brought in 2015; $676,790 of that sum came from people never even charged with a crime.

The FAIR Act proposes to tie forfeiture to criminal convictions, while wisely creating exceptions for certain cases where obtaining one may be impossible—the death or flight of a defendant, for example, or a grant of immunity in exchange for testimony.

It would also buttress these new protections by dramatically limiting the ability of Alabama agencies to participate in the federal equitable sharing program. Utilizing this loophole, authorities can seize property locally, transfer it for forfeiture under comparatively lax federal laws, and then get paid up to 80 percent of the resulting proceeds. In the last 10 years, Alabama agencies have received more than $50 million, according to the Justice Department—money that can only be spent for “law enforcement purposes” and is beyond the control of state and local legislators.

Crucially, the legislation also proposes to bring transparency to the forfeiture process through mandatory, comprehensive reporting, allowing Alabamians to easily determine the circumstances in which forfeiture is used, and how any resulting funds are being expended.

Nationwide, a broad, bipartisan consensus is forming that civil forfeiture laws have become too powerful, too stacked against innocent property owners, and too prone to abuse.

Half the states have taken action to address these concerns—not to inhibit legitimate law enforcement efforts, but to protect the innocent and ensure accountability. Alabama should not shy away from joining this effort.

This piece originally appeared in Yellow Hammer