Civil asset forfeiture is a dangerous tool

South Africa’s civil forfeiture law is based on American law with a long history going back to feudal times, and even earlier. Then, as now, it is easily abused to seize assets from suspects who prove to be innocent, for the enrichment of the state. It should have long gone the way of absolute monarchs.

In early 2013, a mansion in La Lucia, 25 luxury vehicles and 35 other vehicles belonging to S’bu and Shauwn Mpisane were seized by the Asset Forfeiture Unit. It did so under the Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA), which permits the preservation of assets belonging to defendants in criminal cases, the seizure of assets belonging to people who have not even been charged with a crime if there is reasonable belief they will be charged, and the outright forfeiture of any assets that are believed to be instrumental in the commission of a crime or the proceeds of unlawful activities. In each case, the matter is civil, not criminal, which means that the standard of evidence is on a balance of probabilities, not beyond reasonable doubt.

In the case of the Mpisanes, fraud charges were brought against Shauwn Mpisane, but were subsequently dropped, and her freezed assets had to be returned a year later. Whether or not either of the two were actually guilty is not at issue here. The issue is that forfeiture can happen to people who, legally, remain innocent of any charges.

It is not unreasonable for convicted criminals lose their assets to the state. Other forms of forfeiture, such as assets subject to a contract which has been breached, or objects that are criminal by their very nature (such as illicit drugs or plates to print forged money) are likewise uncontroversial. In civil forfeiture, however, privately owned assets can legally be confiscated by the state even when no crimes have been proven against the defendant.

In South Africa, forfeiture actions are based on the discretion of judges, according to Vinesh Basdeo, a law professor at Unisa, which might get around the constitutional injunction that “no law may permit arbitrary deprivation of property”. However, the presumption of innocence principle “poses the most serious constitutional challenge”, he writes, because POCA sets a lower standard of evidence for forfeiture than for criminal convictions.

There is a good reason why criminal proceedings require a court to be convinced “beyond reasonable doubt” of the defendant’s guilt. Any lesser standard of evidence would risk the conviction and possible imprisonment of many innocent people. That there is no similar standard for asset forfeiture should make all of us afraid, because that means that innocent people can be robbed of their assets by a revenue-hungry state.

South Africa’s POCA is based largely on the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisation (RICO) Act in the United States. There, attorney-general Jeff Sessions recently called for an asset forfeiture oversight chief, after a revived policy that allows police at all levels of government to seize assets based merely on “probable cause to believe a crime was committed” raised alarms about civil liberties.

Writes Sarah Lynch for Reuters:

“Under the policy, the government can seize assets from people even if they are never convicted of any crime. In an arrangement with the Justice Department, law enforcement agencies can keep some of the assets they seize. The Obama administration had rolled back the policy in 2015, amid widespread criticism that it was creating incentives for police forces to seize funds and trampling people’s rights.”

Obama’s attorney-general, Loretta Lynch, called civil forfeiture laws “useful”, despite the fact that they offer dramatic examples of perverted justice.

Frank Ranelli, a computer shop owner in Alabama, was arrested on suspicion of receiving a stolen laptop. The charge was dismissed after it was found he had followed proper procedures. However, during the arrest – which required 20 police officers, some armed in full SWAT gear – the police confiscated more than 130 computers, including his administrative machines, those for sale, and those belonging to customers who had brought them in for repair. This happened in 2010. It is now 2017, and he is still waiting for the seized computers to be returned. “The police just fucked my life,” he told a local news outlet.

In New York, Gerald Bryan’s home was searched without a warrant, and he was arrested on drug charges. Police had seized $4,800 (about R66,000) in cash. The charges were dropped, but Bryan never got his cash back. It had already been deposited into the NYPD’s pension fund. In the same city, Kaleb Hagos had almost $3,000 (over $40,000) and an iPhone confiscated. The charges against him were dropped, but his property has not been returned to him, leading to a class-action lawsuit brought by a public interest organisation, the Bronx Defenders.

In Pennsylvania, police routinely seize homes and cars from supposed suspects in drug crimes. One such suspect was a 22-year-old man who lived with his parents and was accused of selling $40 worth of heroin. Six weeks after his arrest, police returned to the scene of the crime and confiscated the house, leaving the parents and siblings homeless. The basis for the seizure was that the property had been used in the commission of a crime, which is also valid grounds for forfeiture under South African law.

Alda Gentile was a passenger in a car stopped for speeding in Georgia. She was not arrested or charged for any crime, but was relieved of $11,530 (about R160,000) in cash that she carried to go on a house-hunting trip. She spent days on the phone to get her money back.

Tan Nguyen was robbed of $50,000 (about R690,000) in casino winnings in Nevada. In another case in that state, $2,400 (R33,000) was seized from Matt Lee. Both occurred during routine speeding stops. According to the county district attorney’s office, the stops were “legally made” and the cash “lawfully seized”. Federal courts disagreed with them, and ordered the return of the two victims’ property.

While driving through the state of Tennessee, George Reby was pulled over for speeding. He had $22,000 (about R300,000) with him to buy a car, for which he could show active bids on eBay. The money was taken off him, on the grounds that it was suspicious to carry large amounts of cash, and his defence about the car buying was not entered into the police report. It took a media investigation, another return trip from New Jersey to Tennessee, a promise not to sue, and four months, to get the money back.

In Wisconsin, Beverly Greer scrounged together $7,500 (about R100,000) in cash to pay bail for her son, who had been arrested on drug charges. The police had specifically instructed her to bring cash. When she turned up, however, they took her money, on the grounds that a drug-sniffing dog detected drugs on the cash. (As if any cash is free of cocaine.) It took a four-month legal fight to get the money back. Jesus Zamora was not so lucky. His girlfriend borrowed cash from friends and co-workers to come up with his $5,000 bail, but it was promptly confiscated as the proceeds of crime. He was not released, nor was the money ever returned.

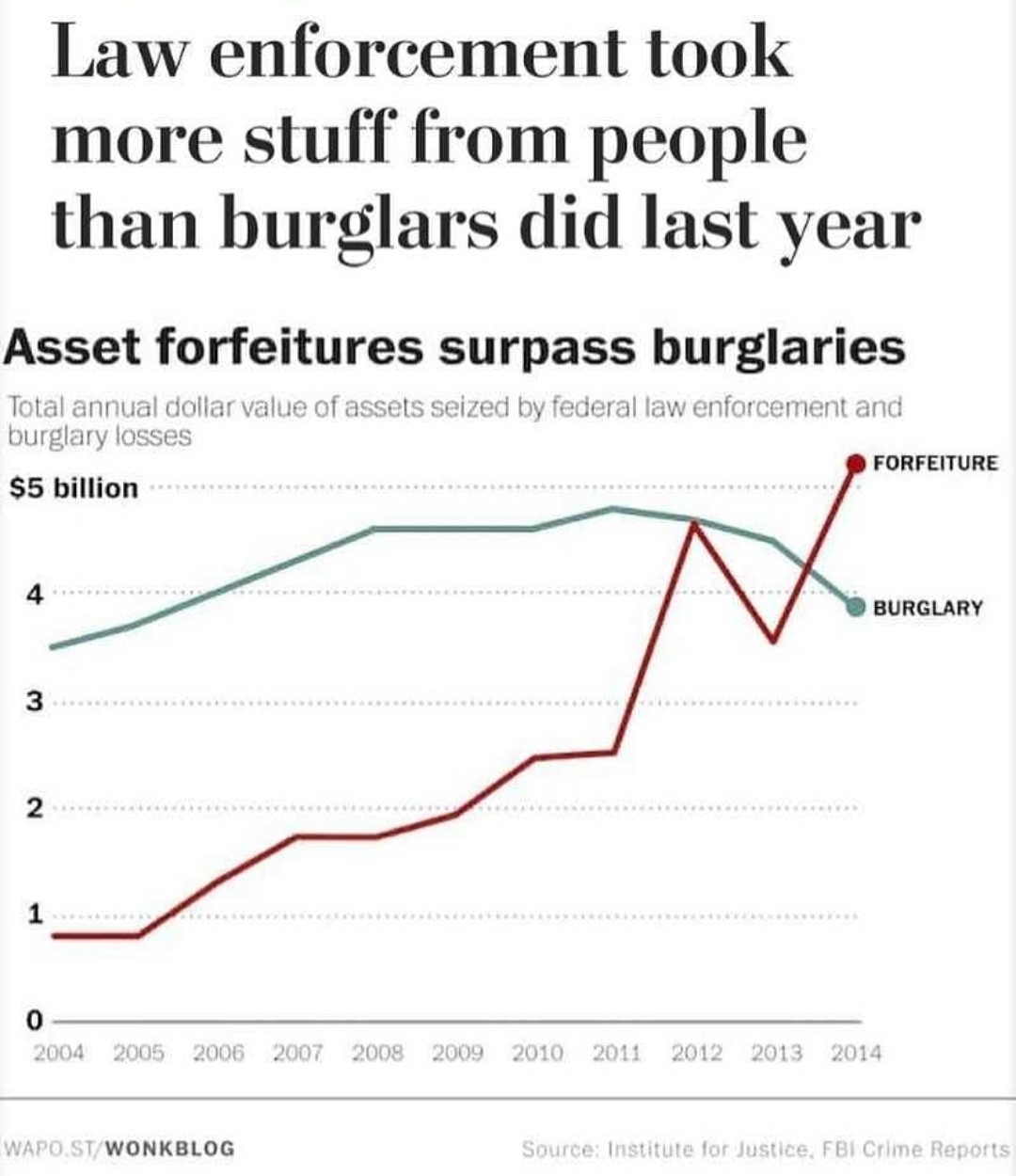

A study by Sarah Welling of the University of Kentucky, and Medrith Lee Hager, a lawyer, concludes that civil asset forfeiture is a billion-dollar business, and the incidence is rising. They estimate that in 80% of civil forfeiture cases, the victim is never charged with a crime, which also means they do not get court-appointed legal representation. “[M]any feel that they cannot afford to reclaim the property,” they write. In the meantime, law enforcement agencies had become increasingly dependent on the revenue generated by civil forfeitures, the study finds.

In 2013, New Yorker magazine ran a long feature investigating the rise of civil asset forfeiture in the United States, often targeting poor people who are intimidated by the police and are unable to fight trumped-up charges.

In the class-action lawsuit brought by Kaleb Hagos’s lawyers in New York, a judge exclaimed: “That’s insane,” when told that the city’s police department did not have any backups of its data on civil forfeitures, and that its computer system is incapable of producing reports accounting for these seizures. So far, the police has stone-walled every attempt to make its records on asset seizures public.

These cases serve as a warning: even in a rich, developed country, one cannot trust governments with civil forfeiture powers. Perhaps South Africa shouldn’t be so keen to copy laws from a country where these powers are so often abused.

Our law might reasonably provide for asset preservation pending a trial, and confiscation of the proceeds of crime upon conviction, but seizing assets without even bringing charges or securing convictions is a recipe for corruption. Forfeiture of assets used in the commission of a crime can also violate the principle of proportional punishment.

Abuse of civil asset forfeiture power risks turning the police, whom citizens are supposed to trust and respect, into feared highway robbers.

“In South Africa”, writes Basdeo, “the courts have accepted a policy rationale based on the fact that it is often impossible to bring the leaders of organised crime to book in view of the fact that they invariably ensure that they are far removed from the overt criminal activity involved. An effective operation against organised crime generally succeeds in bringing only the eminently replaceable foot soldiers to book. Asset forfeiture circumvents and bypasses this problem by allowing the gains of an unlawful enterprise to be brought to justice.”

This may sound like a convincing argument, because nobody has sympathy for crime bosses, but it really is very troubling. It dispenses with the presumption of innocence and punishes people the state has not been able to convict of any crime. It is inevitable that this practice will, by accident or with malice aforethought, target innocent people.

The history of civil forfeiture goes back a very long way, according to Izelde van Jaarsveld, who at the time was an associate professor at Unisa. She notes it was abused to raise royal revenues as long ago as the early 12th century, under the rule of English king Henry I. The Magna Carta, that ancient symbol of personal liberties against an all-powerful state, included provisions to protect the nobility (although not the people) from civil forfeiture.

“Historically, civil forfeiture was introduced as a penal measure, although it later evolved as a way to enrich the Crown. Current civil forfeiture measures are likewise born out of desperation to address crime and punish offenders,” she writes. The troubling implication is clear.

Just like the Magna Carta, modern bills of rights are written to protect citizens from their government. If we don’t want to see the sort of abuses happening routinely in the US, the power of civil asset forfeiture should be tested against constitutional protections, and curtailed where it tramples on people’s rights. Mind you, New York’s statute on civil forfeiture was declared unconstitutional in 1972, and again in 2001. Legislators blithely ignored the courts. It’s not like governments really care about such niceties as civil rights when their own revenues are at stake.

![CF-5-1000×556[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/CF-5-1000x5561-1.png)