Dirty money: How asset forfeiture is returning billions to the federal coffers

It’s like an unforgettable scene from the television crime drama, Miami Vice — Detectives Rico Tubbs and Sonny Crockett pursue some of the biggest drug dealers and smugglers from around the world.

Except it’s not the 1980s. Criminals are now more sophisticated with their crime rings, and it takes more than one unit to bring them to justice.

Inside the Department of Justice, various teams are working together day-in and day-out to capture criminals and seize the items they treat themselves to because of their illegal activity.

Join us Jan. 4 at 2 p.m. EST for a discussion with agency and industry leaders on how data strategy can improve agency mission outcomes, sponsored by LexisNexis. | CPE credit eligible

In part one of Federal News Radio’s special report, Rainmakers and Money Savers, we take an inside look at how much money is brought into the federal coffers due to the work of a specific group of federal employees.

Tracking the money

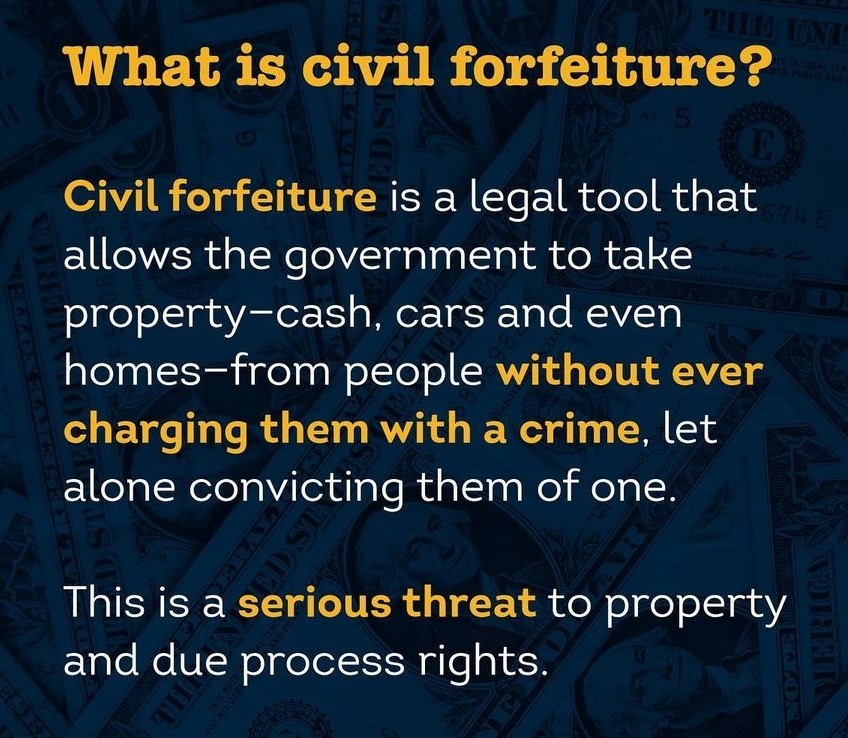

Special Agent Michelle Rankin is a member of the Asset Forfeiture Squad at the FBI’s Washington Field Office. The squad is not only responsible for investigating crimes, but also seizing items associated with criminal activity.

“The typical day is that there is no typical day. Whatever you start off to do at the beginning of the day, the day always dictates something different,” she said.

Perhaps it’s because each agent on the Asset Forfeiture Squad manages a caseload of 50 to 80 cases. All are in various stages of investigation.

To try to move the investigation along, agents use a variety of tools, some taught through cross programming at FBI headquarters. They include interviews, information subpoenaed by grand juries, surveillance reports, law enforcement databases, Department of Motor Vehicles records and social media.

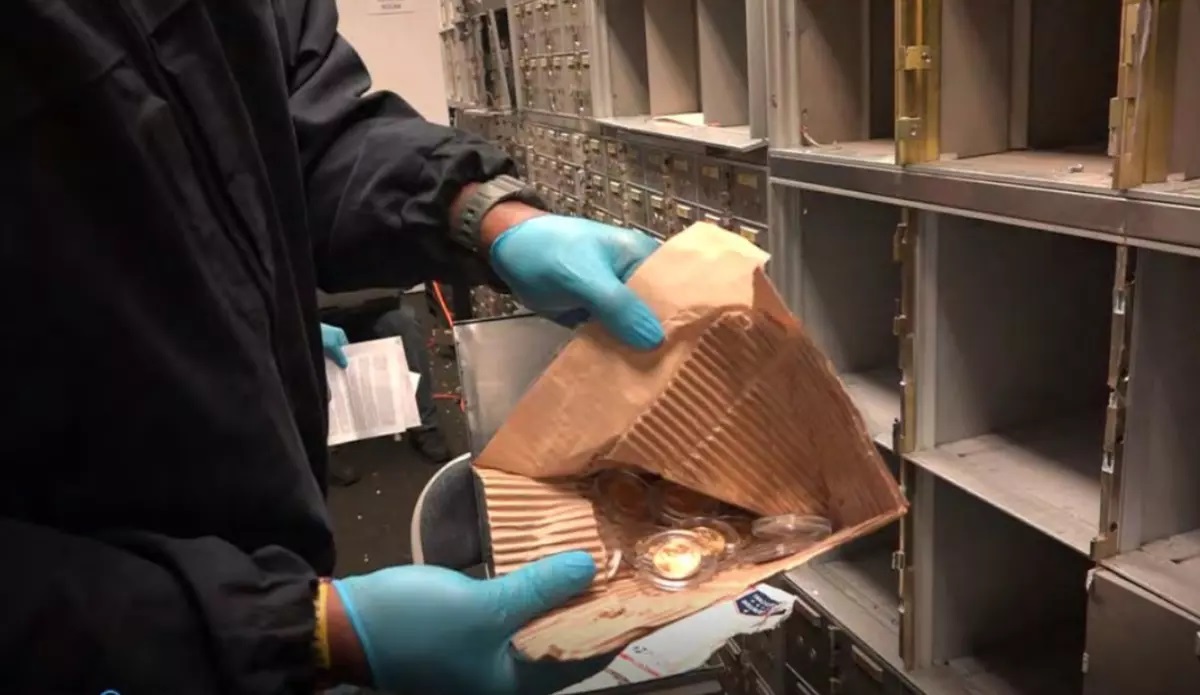

Once an investigation is over, the FBI turns all assets over to the U.S. Marshals Service, unless it needs the assets for an ongoing investigation.

The Marshals Service is then responsible for taking care of the asset and planning the best way to sell it. Commercial businesses, antiques, planes, boats and collectibles are all included.

Read more: Management

In FY 2013, the service sold more than 22,000 assets for a total of $2 billion. $200 million was returned to crime victims, while $571 million was shared with participating state and law enforcement agencies that helped with the cases.

Jay Ramaswamy, chief of the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section in the Criminal Division of the Justice Department, knows these statistics all too well. He has his hands in each and every case.

Ramaswamy and his colleagues are responsible for setting policies for the program, paying out forfeited money to victims, and making recommendations along with the Justice Management Division about how to reinvest forfeited money to other law enforcement components.

When analyzing the success of the program, he says, “The annual net intake of the Asset Forfeiture Fund year-over-year is in the $1.5 billion range. Just on that, you can see that the program has grown exponentially. At this point, the program itself, and running the program, is like running a Fortune 500 company given the amount of forfeiture. That doesn’t even include the amount of money that’s returned to innocent third parties such as victims.”

Things that make you go “hmm …”

The amount of money collected by all of the asset forfeiture programs is high, because sometimes collecting the assets comes easy depending on a criminal’s actions.

Want to stay up to date with the latest federal news and information from all your devices? Download the revamped Federal News Network app

“You’d be surprised at how many people will take a picture of themselves on Facebook with some fancy asset they have, and that gives us a clue to start investigating,” Rankin said.

Ramaswamy said he’s been a part of plenty of historic seizures, including one in Texas where horses were being used to launder drug proceeds.

“As you can imagine, forfeiting livestock has a lot of perplexity as far as feeding them, caring for them and that’s something that the Marshals Service does very well,” Ramaswamy said. “I remember a few years ago there was a prosecution out of New York where a landmark there, the Tarrytown Castle, which is used for weddings, was forfeited as part of an ongoing investigation. It had to be run like a business in order to preserve its value while that was going on. … And so there’s been everything from wildstock to memorabilia to business that have been forfeited.”

Rankin has had her share of interesting seizures as well, including one where a suspect used part of the money he stole to purchase a lottery ticket. The lottery ticket ended up being a winner.

The winning formula

To keep bringing money into the government and distributing it where it needs it most, the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section has three new priorities going forward that will affect all of the assest forfeiture programs under DoJ in different ways.

Ramaswamy says DoJ is focusing on officers in financial institutions that are laundering proceeds or allowing dirty proceeds to flow through financial institutions. This includes money service businesses, banks, brokerages and casinos.

Secondly, DoJ is focusing on third-party money launderers who disguise themselves as attorneys, accountants and bankers. They are usually in bed with organized crime and help move the money off shore.

Third, is the agency’s Kleptocracy Initiative, which looks at foreign corruption proceeds that have worked their way into the U.S. financial system.

“By attacking foreign corruption and foreign proceeds, we’re attacking the financial infrastructure that services both them, as well as organized criminals around the globe,” Ramaswamy said.

![uk-crypto-crime[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/uk-crypto-crime1.jpg)

![igor-groshev-adobe-stock-140622[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/igor-groshev-adobe-stock-1406221.jpeg)

![cop_hand_up_000018137672XLarge[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/cop_hand_up_000018137672XLarge1.jpg)