Good and bad news on civil asset forfeiture

Good and bad news on civil asset forfeiture

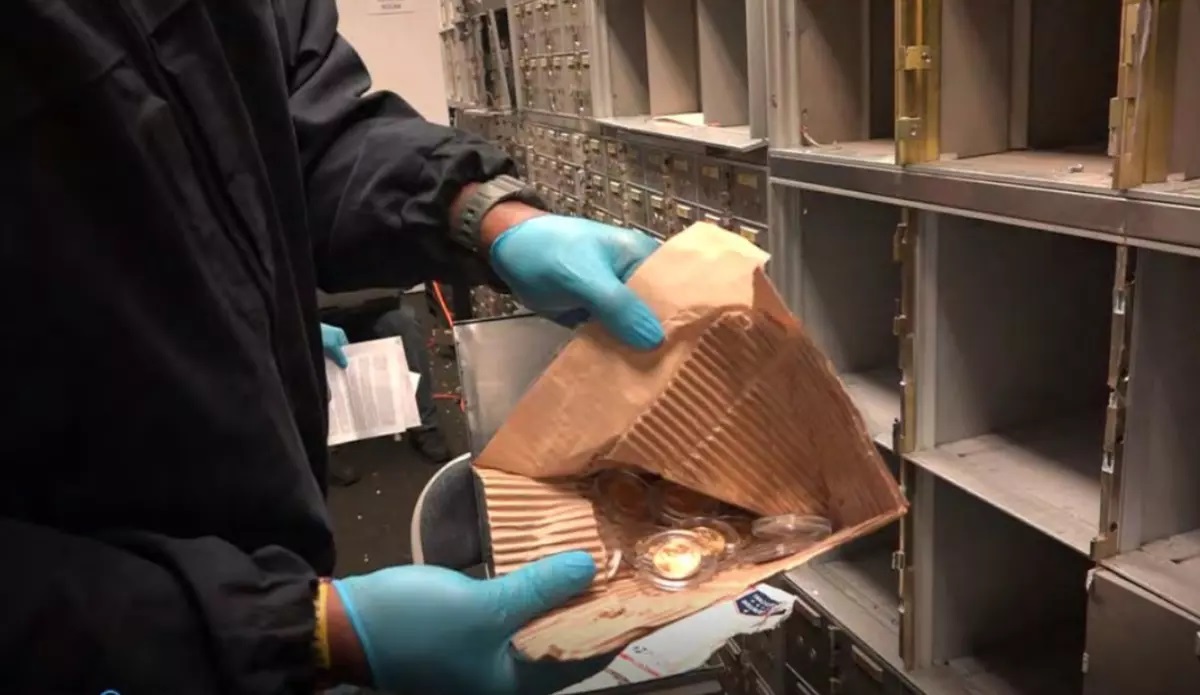

Saraland, Ala., police show off bundles of cash seized in an April 2008 traffic stop on Interstate 65.

Saraland, Ala., police show off bundles of cash seized in an April 2008 traffic stop on Interstate 65.

Author

By ORANGE COUNTY REGISTER | Orange County Register

January 5, 2017 at 7:21 a.m.

There have been both positive and negative developments on the issue of civil asset forfeiture.

That’s the controversial practice whereby police seize one’s cash, vehicle, home or other assets, often without any charges being filed, much less a conviction of a crime.

The state of California took a step in the right direction when it passed a compromise measure, Senate Bill 443, last year that requires a conviction before state or local police seize property worth less than $40,000 (the previous threshold was $25,000), increases the government’s burden of proof for these cases from “clear and convincing evidence” to “beyond a reasonable doubt” and plugs a loophole in state law that allowed police to partner with federal law enforcement agencies through “equitable sharing” arrangements to keep more proceeds from seizures (up to 80 percent, versus the 66.25 percent limit under state law) and operate under more lax rules.

There is still room for improvement, though. Why is it unacceptable and a violation of one’s rights to seize $30,000 of property without a conviction, but perfectly all right to seize $300,000? If anything, it seems that law enforcement agencies looking for some extra revenue would target these bigger-ticket items anyway.

An even better approach would be to eliminate such perverse incentives and abolish the practice altogether, as New Mexico did in 2015.

There have been other victories around the country, too. Last week, Ohio enacted a forfeiture reform law limiting the practice. Now roughly one-third of the states prohibit or strictly limit civil asset forfeiture.

There have even been happy endings in some high-profile asset seizure cases. For example, two California poker players who had their $100,000 in winnings taken during a traffic stop in Iowa, under the guise that the cash must somehow be connected to drug trafficking, reached a settlement in their lawsuit against the state whereby the state will pay them $60,000 on top of the $90,000 that it had previously returned to them. In addition, the Iowa State Patrol decided to disband the entire “interdiction team” responsible for the seizure.

Not all of the news is positive, however. During a November House Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing, Justice Department Inspector General Michael Horowitz and U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration spokesman Melvin Patterson both admitted the DEA’s civil forfeiture policies suffer from “Fourth Amendment issues.” Horowitz acknowledged concerns that “the DEA’s policies are warping priorities by prioritizing asset forfeiture rather than the seizure of drugs.”

In addition, the Institute for Justice has filed Freedom of Information Act lawsuits against the Internal Revenue Service and U.S. Customs and Border Protection over their refusal to provide information about the federal government’s forfeiture activities.

Civil asset forfeiture is just one more example of the negative unintended consequences to come out of the failed “war on drugs.” When a law enforcement agency can act as judge and jury, and keep the assets they seize, without even the burden of proof that binds a judge or jury, where mere suspicion — real or feigned — is adequate to take one’s assets, it is a miscarriage of justice. California is on the right path, but it should not stop until it puts an end to this much-abused system.

![pfp_social[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/pfp_social1.jpg)

![original[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/original1.jpg)

![GettyImages-172327317[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/GettyImages-1723273171.jpg)