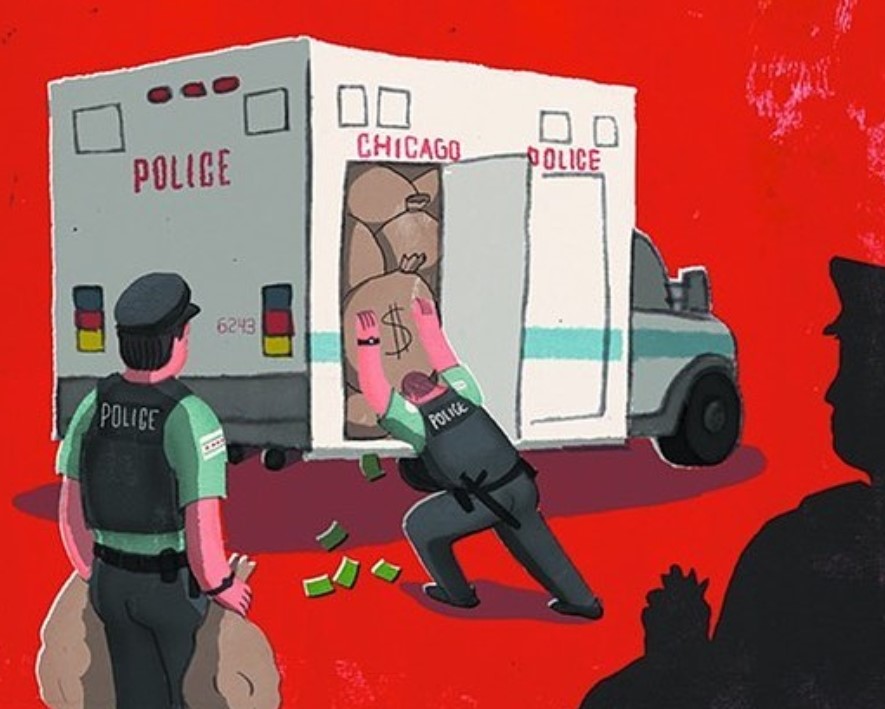

How Civil Asset Forfeiture Turns Authorities into ‘Bounty Hunters’

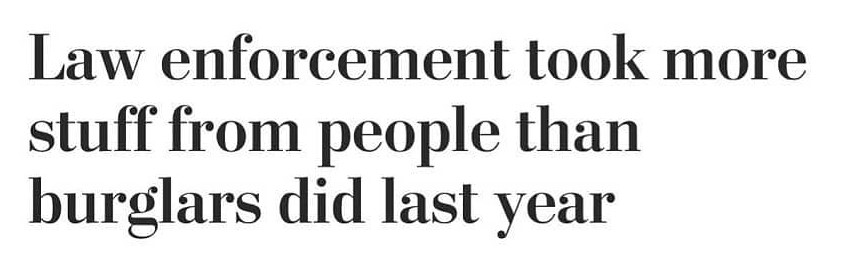

Civil asset forfeiture gives police officers the right to seize cash, cars and homes from people who haven’t been convicted of a crime, which is why it’s time to end this exploitative practice by passing laws that prohibit it, argues the USA Today Editorial Board.

Intended to reduce crime by seizing the profits of drug dealers, civil asset forfeiture has become a legal way for officers to pocket the property of mostly poor and innocent people, the editorial says.

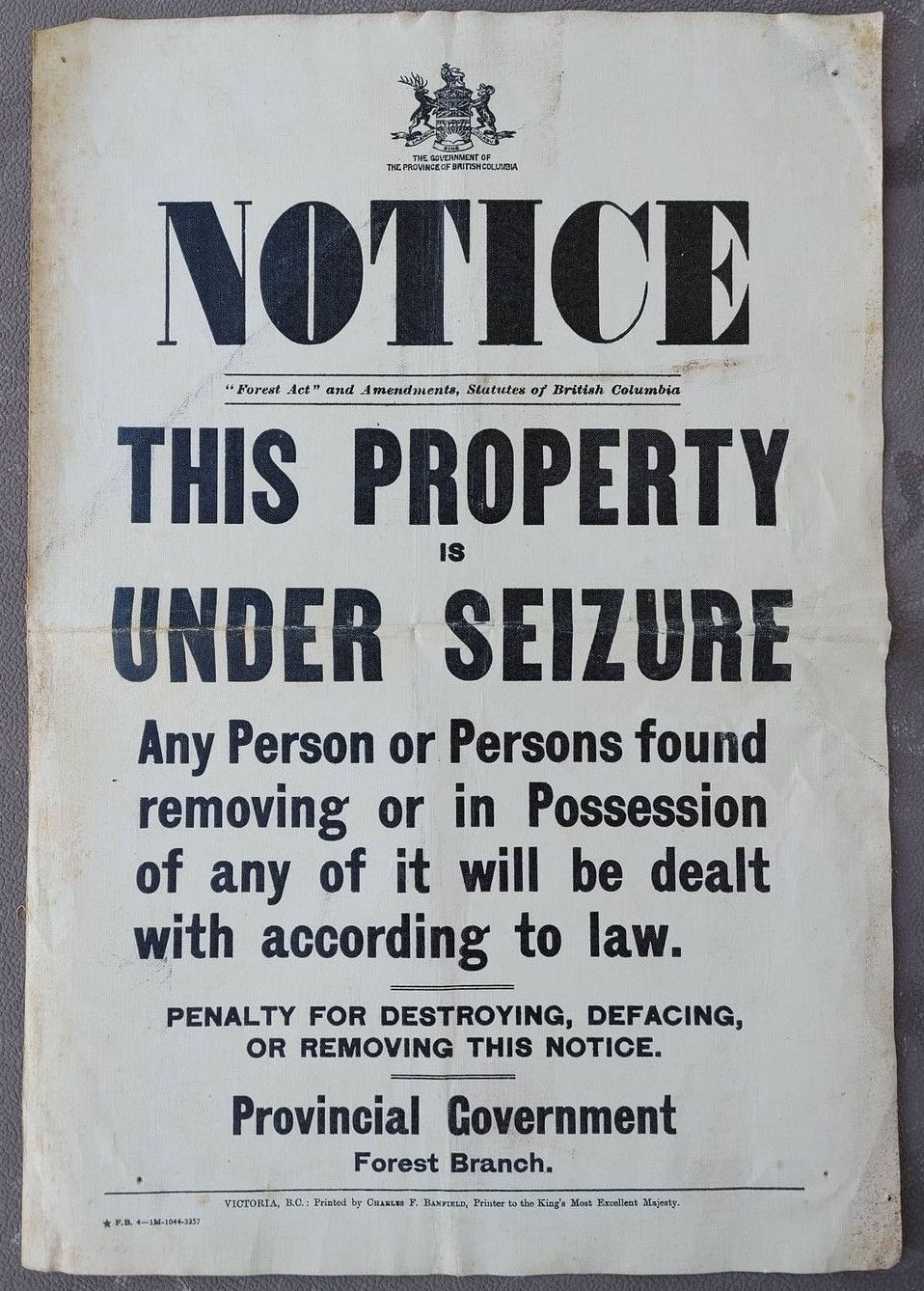

The practice, which skirts the Fourth Amendment’s protection from unreasonable searches and seizures, allows police to confiscate property they believe is connected to a crime — even if they don’t charge the property owner with criminal activity.

Rather than direct the funds elsewhere, federal, state and local authorities keep all or part of their forfeitures. Since 2000, authorities have amassed a total of $69 billion in forfeiture revenue, according to an Institute for Justice report.

The St. Louis County Police Department used $170,000 in asset forfeiture money to buy a BEAR (Ballistic Engineered Armored Response) tactical vehicle in 2001. The county also spent $400,000 in forfeited money on helicopter equipment in 2011, according to The Pulitzer Center.

The practice privileges law enforcement in other ways: once police seize assets, it’s up to the former asset owner to prove the assets are unconnected with a crime.

Additionally, a federal loophole lets law enforcement agencies circumvent state restrictions on the use of forfeited property through the federal Equitable Sharing Program, under which the Justice Department adopts a forfeiture and sends up to 80 percent of the money back to local law enforcement to spend, reports The Pulitzer Center. By withholding all money for law enforcement, the federal Equitable Sharing loophole limits funds for schools.

The average size of a forfeiture — usually targeted on cash impoundments — is $1,276, according to an earlier Institute for Justice report.

Low-income Americans, many of whom don’t have bank accounts, are often targets of civil asset forfeiture and struggle to afford a lawyer to recover lost assets.

Several prominent cases have demonstrated the failure of civil asset forfeiture. In 2019, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seized $82,000 from Rebecca Brown — her father Terry Rolin’s life savings — at an airport as she was bringing the money to Boston to open a joint bank account. Working with pro bono lawyers and filing a class action lawsuit against the government, Brown and Rolin recovered the money six months later, reports The Washington Post.

In another high-profile case, sheriff’s deputies in Muskogee County, Oklahoma seized over $53,000 in cash from a Burmese Christian rock band that had raised money for a Christian college in Myanmar and a Thai orphanage, reports The Washington Post.

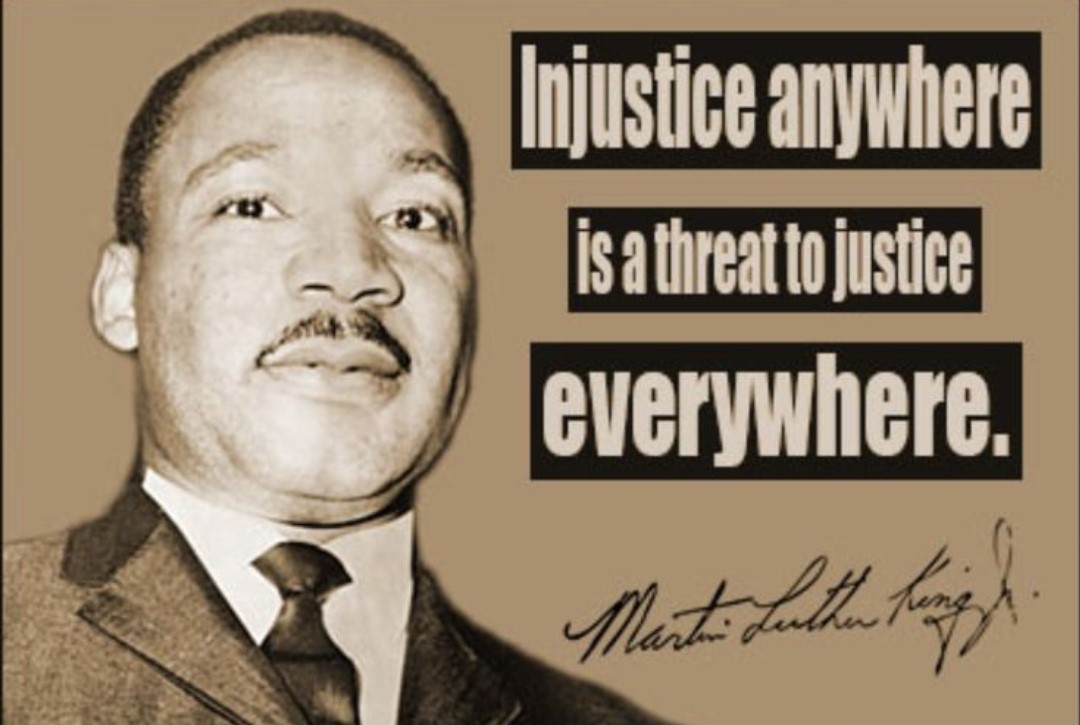

“Civil asset forfeiture turns authorities into bounty hunters who somehow can’t imagine the many legitimate reasons people carry cash,” the USA Today Editorial Board writes. “They’ve snatched large amounts of cash from people carrying it to buy a used car, to close a business deal or simply because it’s the proceeds of their legitimate cash business.”

Three dozen states have passed laws limiting the scope of civil asset forfeiture — but with more restrictions comes a greater reliance on legal loopholes. Still, some states have passed laws that preempt loopholes: a 2015 New Mexico law requires conviction before officers permanently take money or property and mandates all proceeds go into the state’s general treasury rather than directly to police, reports Forbes.

Maine became the fourth state to abolish civil forfeiture this week, authorizing forfeiture only after a criminal conviction, reports Forbes. In Maine, half of all cash forfeitures were under $1,670.

In addition to urging other states to pass laws banning civil asset forfeiture, the USA Today Editorial Board said Congress should eliminate federal agencies’ use of civil forfeiture and end the loophole program that allows sharing with states.

“Forfeiture is one more reason many law-abiding citizens fear and distrust law enforcement,” they write. “In America, no one like Terry Rolin or his daughter should have to battle the government to get back their hard-earned property.”

Eva Herscowitz is a TCR Justice Reporting intern.