Mooresville Police Face Legal Fight Over Cash Seized From Suspects

A judge in Statesville last week barred Mooresville police from doing something that’s increasingly common among local police departments in North Carolina: turning over cash seized from suspects to the federal government. In 2019 alone, police departments in the state got back more than $12 million through what’s known as the Equitable Sharing Program.

The order by Superior Court Judge Mark Klass was a victory for two Statesville men — Shyheim Summers, 21, and Tavis Da’Shawn Dulin, 23 — because it kept the money out of the hands of the federal government. It says Mooresville police must hold onto $14,000 that officers took from the men May 27, after they were questioned about a possible shoplifting.

On June 9, they were arrested on charges that included possession of marijuana with intent to sell. Their lawyer is Ashley Cannon.

“The practice of civil asset forfeiture allows the government to just take money from private citizens,” Cannon said. “And we certainly don’t feel like the government should have the ability to go in and take assets from people without any just cause. And they’re doing that routinely, at least in Iredell County.”

State Vs. Federal Law

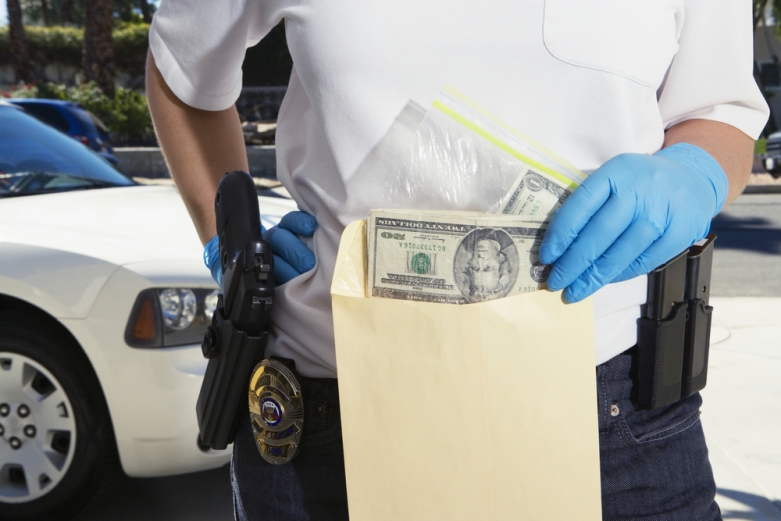

Police often seize cash, cars and other assets during investigations. State law says police departments must keep those assets and be prepared to return them if defendants are acquitted.

But federal law is different — it doesn’t require the return of seized property. So departments often skirt state law by signing assets over to the federal government in exchange for a cut of the proceeds later.

[RELATED: Asset Forfeiture Creates ‘Perverse Incentive For Police To Profit’]

Police cruisers outside Mooresville Police Department.

David Boraks

/

WFAE

Police cruisers outside Mooresville Police Department.

“As soon as they turn the money over to the federal government, even if he’s found not guilty, or the charges are dismissed, the federal government still keeps the money,” Cannon said.

That’s why Cannon took the unusual step of asking Klass to block Mooresville from handing the money over to the federal government. Town spokesperson Kim Sellers said Mooresville has been holding the money and “we have no issues with continuing to do so.”

But Mooresville police are fighting back in another case involving Cannon. In November, officers took about $17,000 from a Connecticut man, Jermaine Sanders, whom they suspected of smoking marijuana in his car. A day later, they charged him with possessing a small amount of marijuana.

Through his lawyer, Cannon, Sanders asked for his money back. Two judges in Statesville agreed and ordered Mooresville to return the money. When the town refused, a judge eventually held the town and police department in contempt of court.

In the meantime, police gave the money to the Department of Homeland Security. They say they took the cash because they suspected Sanders of dealing drugs — even though he wasn’t charged with that.

Cannon said the law forces defendants to fight to get back their own property.

“So it’s sort of like, we’re gonna take your property, your assets, your money, and you’re gonna have to prove to us why we shouldn’t be able to keep it,” she said.

A Local Share Of The Proceeds

Under the federal Equitable Sharing Program, up to 80% of asset forfeitures are kicked back to local departments, which critics say gives police an incentive for more seizures.

Many departments, like Mooresville’s, count on the revenue. In the past two years, the Mooresville Police Department has gotten back about $40,000 a year from asset forfeitures. So far this year, they’ve collected $93,000 in state and federal seizures.

Raleigh lawyer Elliot Abrams, who also handles asset forfeiture cases, calls that kind of arrangement “unbudgeted money, in essence, what … some people might call a slush fund for police to do whatever they want with. And a lot of that money is used to buy the things that we then would say are driving the militarization of police.”

This year, Mooresville used $15,000 from its asset forfeiture accountto buy a system that lets officers shoot a GPS tracking device from their cruisers that attaches to speeding or fleeing vehicles.

The town of Mooresville declined to make anyone available for an interview. The town says its seizures are lawful.

Meanwhile, Sanders’ misdemeanor case is scheduled for trial in July. The dispute over his $17,000 is now in federal court and the state Court of Appeals.

![459902226.0[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/459902226.01.jpg)

![21f131b7-28f4-4147-8829-e7d6e983da8e-Civil_forfeiture_supreme_court_JRW02[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/21f131b7-28f4-4147-8829-e7d6e983da8e-Civil_forfeiture_supreme_court_JRW021.jpg)

![skynews-kim-kardashian-reality-tv-star_5918849[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/skynews-kim-kardashian-reality-tv-star_59188491.jpg)