Op-Ed: Weak reforms allow Arkansas police to patrol for cash

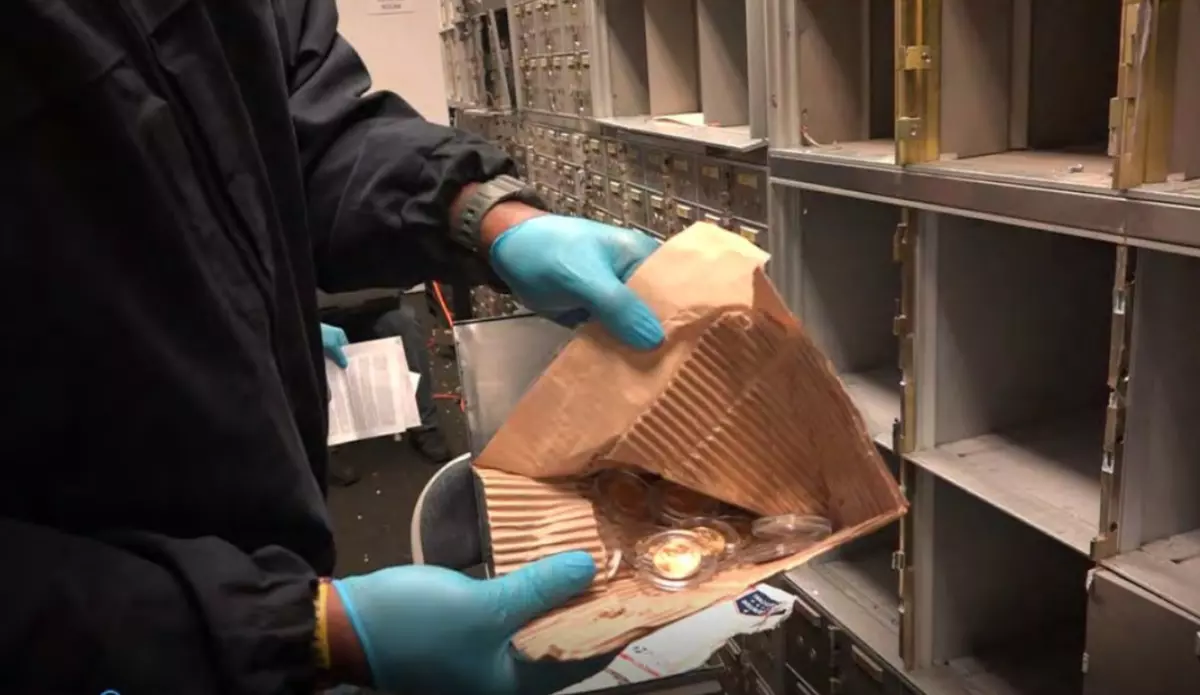

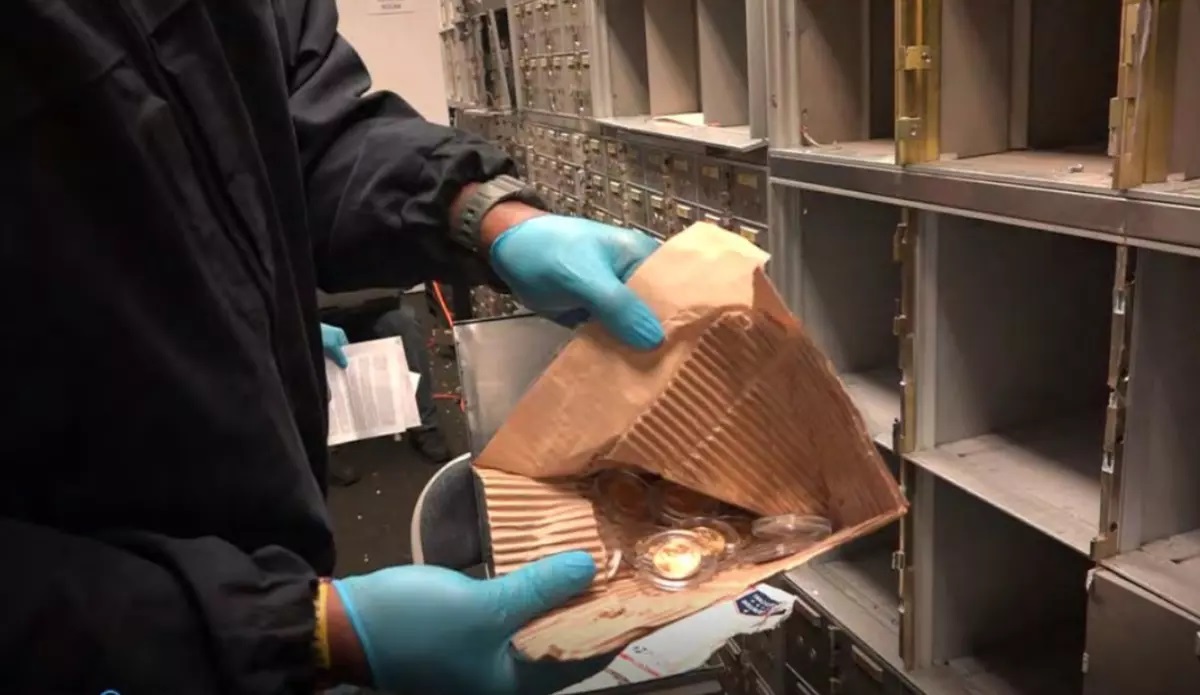

Guilt or innocence does not always matter when the government decides to take private property in Arkansas. Guillermo Espinoza learned the hard way while driving through the state in 2013.

A state trooper stopped Espinoza’s vehicle near Malvern and conducted a warrantless search, which produced no evidence of wrongdoing. Espinoza, a Texas resident traveling with his girlfriend, carried no drugs, weapons or contraband of any type. But he did have nearly $20,000 in cash.

Despite the lack of probable cause, the trooper seized the currency and transferred the full amount to the state. Espinoza tried to get his money back in the weeks and months that followed, but he failed to file the right paperwork within the narrow windows that the state allows.

Ultimately, he lost his case on technicalities without ever facing arrest or charges. Prosecutors bypassed the criminal courtroom altogether using a process called “civil forfeiture.” The moneymaking scheme allows the government to take and permanently keep assets using civil standards of proof instead.

Arkansas laws have changed since then. Senate Bill 308, which sailed through the state House and Senate in 2019, promised to gut civil forfeiture by requiring the government to win a conviction before going after someone’s property. Unfortunately, the legislative fix has failed to deliver in three important ways.

First, people like Espinoza still can lose their assets by default if they fail to navigate the civil procedures correctly. Many property owners must file paperwork – known as answering a civil complaint – and jump through other hoops while simultaneously fighting criminal charges in a separate court or worrying about the threat of criminal charges.

Essentially, the system pulls people in two directions. And because forfeiture remains a civil matter in Arkansas, property owners have no right to counsel. They must pay for their own defense. Giving up – even without a conviction – often makes the most sense financially when attorney costs outweigh the value of seized assets.

Such a strategic decision is not a rare occurrence. More than half the cash seizures in Arkansas are for less than $1,000, while the estimated cost of hiring an attorney to fight a simple case at the state level is about $3,000. Not surprisingly, nearly four out of five forfeiture cases go uncontested in states that provide the information.

The second flaw with the 2019 reform is the preservation of perverse financial incentives for police and prosecutors. Arkansas allows law enforcement agencies to keep up to 100% of forfeiture proceeds, which turns every public interaction into a potential payday.

Finally, Arkansas law fails to protect innocent third-party owners. If someone loans a vehicle to a person who commits a crime, for example, the government can forfeit the property even if the owner had nothing to do with the illegal behavior.

Recent changes in Arkansas look good on the surface but fall apart under scrutiny. The reform represents, at best, a modest improvement and, at worst, a diversion from the deeper changes needed.

New research from the nonprofit Institute for Justice highlights the negative implications. “Does Forfeiture Work? Evidence from the States,” published Feb. 10, moves beyond the emotion of the policy debate and looks – for the first time – at state-level data using empirical methods.

The findings are troubling. When forfeiture activity increases, police do not solve crimes at higher rates and drug use does not drop. In other words, government cash grabs simply do not work as advertised. Rather than boosting public safety, forfeiture merely boosts revenue for its own sake.

Arkansas deserves better. State lawmakers who voted unanimously for the 2019 reform should try again in 2021 with legislation that ends civil forfeiture once and for all and replaces it with criminal forfeiture. Instead of a two-track system that tries people in one court and their property in another, the law should bring both parts together and force the government to prove its allegations beyond a reasonable doubt.

As a further safeguard, the law should direct all proceeds away from law enforcement. The same people who control forfeiture should not profit from their decisions about what property to seize and what cases to prosecute.

Without these changes, innocent people like Espinoza remain at risk.

![original[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/original1.jpg)

![page1-1200px-Guide_to_Equitable_Sharing.pdf[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/page1-1200px-Guide_to_Equitable_Sharing.pdf1_.jpg)