Police agencies forfeit millions after new law chokes off funds from asset seizures

Jewels worth $7.2 million were seized in Los Angeles. Fine art worth $4.1 million was seized in Signal Hill. U.S. currency totaling $30.8 million was seized in Beverly Hills.

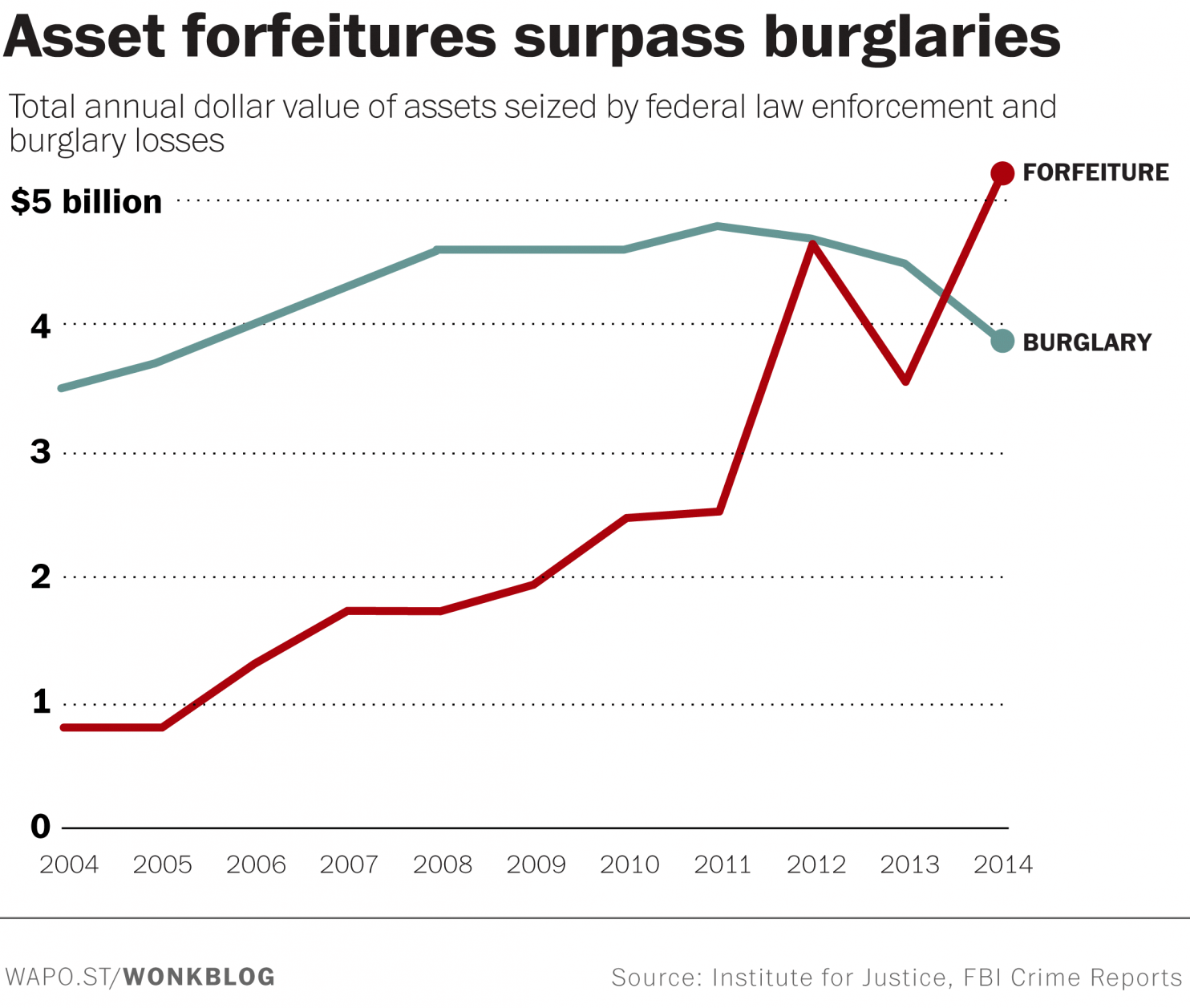

Federal law enforcement operations seized nearly $1.9 billion worth of airplanes, houses, cash, jewelry, cars and other items from suspected wrongdoers nationwide in 2018 — a precipitous drop from $2.6 billion just three years earlier, according to federal data.

While the value of property seized in California has skyrocketed, the state’s share of the booty — which has traditionally helped fund local police agencies — has plunged. That’s largely because of a new state law seeking to protect personal property, allowing local agencies to keep proceeds from asset seizures only when people are convicted of a crime, rather than simply when they’re arrested.

The resulting drop in California’s overall share of these funds has been precipitous. A Southern California News Group analysis of federal data found that:

In 2015, law enforcement operations in California pumped $170.9 million into the Federal Asset Forfeiture Fund, and the state received $86.1 million in “equitable sharing payments” in return. That’s a clean 50 percent cut.

In 2018, California operations pumped far more into the fund — $437.6 million — but the state got back far less, just $55.2 million. That’s amounts to a 12.6 percent cut of the proceeds.

Federal authorities want to seize this building owned by Tony Jalali because he rented out space to a pair of medical marijuana dispensaries. The structure is worth $1.5 million. (Photo by ART MARROQUIN, Orange County Register/SCNG)

Approximately $145,000 was seized by the Garden Grove police department in 2011 during an illegal gaming raid.(PHOTO BY JOSHUA SUDOCK, ORANGE COUNTY REGISTER/SCNG)

Show Caption

of

Expand

Local impacts

Local agencies have lost millions of dollars. For example, LA IMPACT — the Los Angeles Interagency Metropolitan Police Apprehension Crime Task Force — saw equitable-sharing revenue shrink from $6.9 million to $3.7 million from 2015 to 2018.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department share dropped from from $5.3 million to $3.7 million; San Bernardino agencies went from $2.9 million to $258,996; Riverside agencies dipped from $2.1 million to $1.2 million; and in Orange County, the Santa Ana and Anaheim police departments went from $4.2 million to $1.7 million.

Meanwhile, states like Georgia, Iowa, Massachusetts and Kentucky received equitable-sharing payments equal to 100 percent — or more — of what they pumped into the fund last year.

The national average was about 30 percent, according to the SCNG analysis. California did worse than Texas, which received payments equal to 36.3 percent of what it pumped into the fund that year, and New York, which received 22.2 percent.

Law enforcement agencies in California predicted — and bemoaned — the loss of revenue back in 2016, when Senate Bill 443 was signed into law.

Civil rights activists called it one of the nation’s most far-reaching protections against asset forfeiture abuse. But the data suggests that seizures in California haven’t necessarily abated, but rather that local agencies no longer get as big a cut.

‘Theft by cop’

Asset forfeiture was created during the 1980s’ “war on drugs” with the best of intentions — to reduce crime by depriving drug traffickers, racketeers and criminal syndicates of their ill-gotten gains.

But there was no requirement that someone be convicted of a crime before police seized their stuff. Often, no charges were brought at all. Law enforcement’s suspicion that cars and cash were tied to crime was enough for them to keep it.

California eventually passed laws — more stringent than the federal government — restricting when state and local police could seize private property. So local agencies worked around them by partnering directly with the U.S. Department of Justice in asset-forfeiture cases, bypassing the rules in state laws.

SB 443 closes that loophole for state and local agencies — but not for the federal government, which can continue to seize property without criminal convictions.

Critics charge that the asset forfeiture system creates perverse incentives, encouraging the pursuit of property over the impartial administration of justice. They describe the practice with pejoratives like “policing for profit” and “theft by cop.”

Landlord Tony Jalali owned a commercial building in Anaheim in 2012. He rented space to a dental office, an insurance company and two medical marijuana dispensaries. The dispensaries were legal under state law, but Anaheim police teamed up with federal prosecutors and seized Jalali’s building, saying it was linked to criminal activity. Jalali faced the loss of his property, worth some $1.5 million, even though he was never charged with a crime.

The nonprofit Institute for Justice in Virginia took up Jalali’s case pro bono, and after more than a year in federal court, the government dropped the case. But not everyone who gets caught in the system is so fortunate.

California’s stand

The ACLU of California found that more than 85 percent of forfeiture payments went to agencies where people of color made up more than half of the local population. Other investigations have found that minorities, immigrants and low-income communities are disproportionately at risk of having their property seized.

SB 443, by Sen. Holly Mitchell, D-Los Angeles, and former Assemblyman David Hadley, R-Torrance, went into effect in 2017 and aimed to address those inequities. It required a conviction in most cases before state and local law enforcement could permanently keep anyone’s property.

But two years in, the number of federal seizures has increased 13 percent, from 40,426 to 45,855.

“The goal of SB 443 was simple: to rein in policing for profit in California and reestablish some of the most basic tenets of constitutional law and values,” said Mica Doctoroff, legislative attorney with the ACLU of California Center for Advocacy & Policy, in an email.

“In particular, the bipartisan-backed law was designed to prevent California law enforcement agencies from circumventing state law in order to use the federal civil asset forfeiture process to profit off the backs of property owners who have not been convicted of an underlying crime,” Doctoroff said.

“At a time when the federal government has renewed its zeal for policing for profit and the failed war on drugs, California has taken a stand against civil asset forfeiture abuses and sought to protect property owners.”

The Golden State is trying to set a good example and do the principled thing, even as the federal government goes in the opposite direction, said Gregory Chris Brown, associate professor of criminal justice at Cal State Fullerton.

“California is making a point — we are not Trump country,” Brown said. “But the mindset of ‘take the assets, put the criminals out of commission and benefit the department’s coffers’ remains, particularly in the Trump era.”

‘Slashes funding’

State-federal forfeitures have pumped billions into local law enforcement coffers over the past 30 years. After expenses were deducted, much of the proceeds from seized and forfeited booty helped pay police salaries, fund operations and investigations, and buy equipment.

The loss of more than $30 million just from 2015 to 2018 — while the value of property seized in California has more than doubled — hurts, police officials acknowledge.

“Our deputies need the proper resources to conduct investigations, maintain high-quality equipment, and carry out daily operations,” said Ron Hernandez, president of the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, by email. “ALADS opposed SB 443 because it slashes funding that law enforcement agencies use to keep communities safe. We will continue to fight for legislation that properly funds public safety and gives deputies the resources they need.”

In Long Beach, police officials said the reduction in asset forfeiture proceeds has made it more difficult for the department to fund public safety infrastructure such as facilities, technology and field equipment. It has prompted the department to adjust its long-term planning strategies, increasing reliance on the operating budget and other grants, spokeswoman Jennifer De Prez said in an email.

In February, the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution places limits on the ability to seize and keep property linked to crimes. It sided with Tyson Timbs, whose $42,000 Range Rover — financed by his father’s life insurance — was seized after he sold $225 of heroin to an undercover officer in Indiana.

Bryan L. Sykes, an assistant professor in UC Irvine’s Department of Criminology, Law and Society, is part of a multistate study of monetary sanctions. One case cited was that of a man convicted of making threats during an inheritance squabble with his family, and had a collection of antique munitions and weapons worth about $50,000 seized — far in excess of any fine connected to his crime.

Sykes believes there’s more work to do.

“States do not have the right to bow out of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids excessive fines and cruel and unusual punishment,” he said.

![shutterstock_120789925_0[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/shutterstock_120789925_01.jpg)

![459902226.0[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/459902226.01.jpg)