Reasonable limits on asset forfeiture past-due

When law enforcement officials seize property gained through criminal activity, those of us on the right side of the law should applaud. When they seize property from individuals who not only haven’t been convicted of a crime but haven’t even been charged with a crime, something is amiss. A recent Supreme Court decision is a first step toward ending this injustice.

When used properly, “civil asset forfeiture,” as it’s called, enables the government to seize assets from criminals and convert them into assets that can benefit the public.

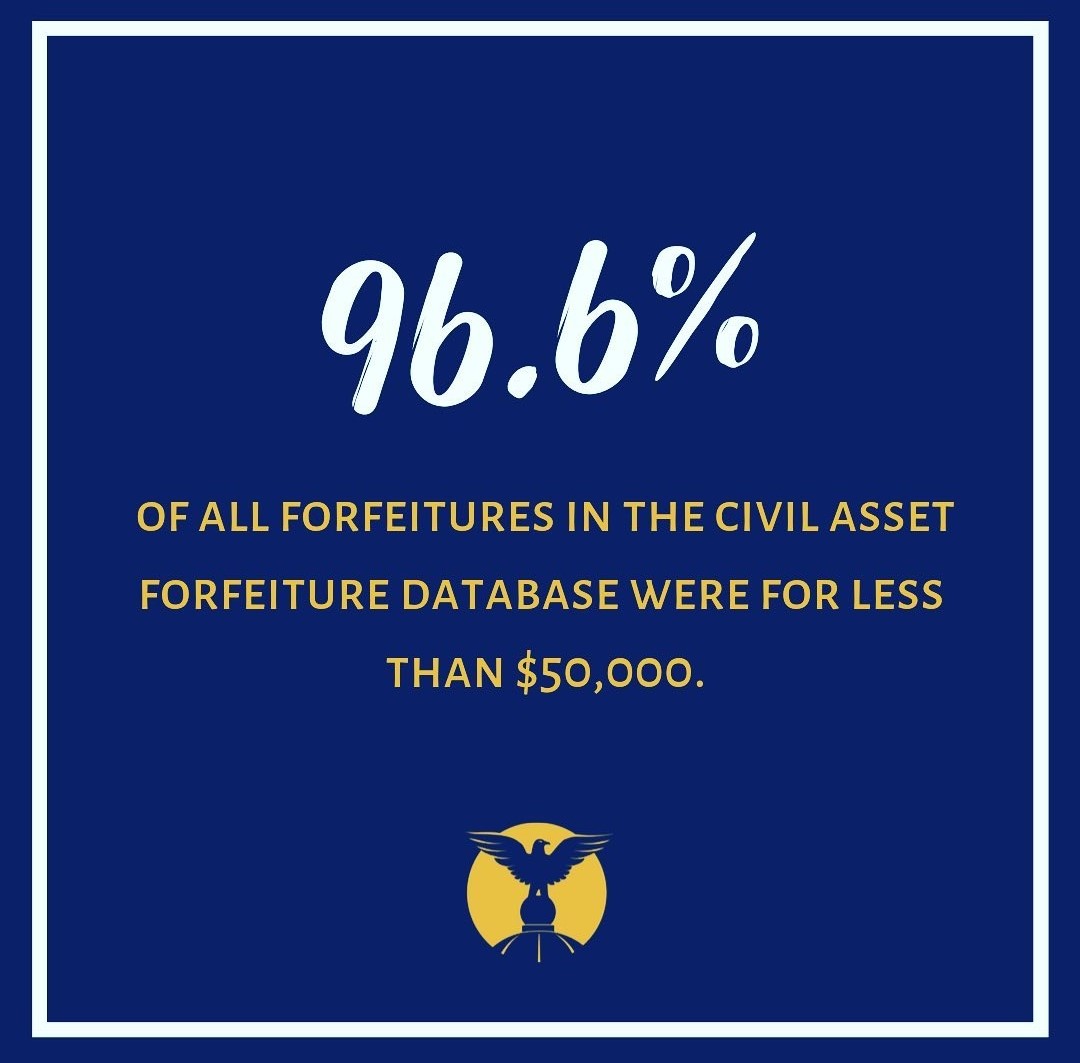

Forfeiture got turbocharged in the 1980s with the escalation of the War on Drugs. It steadily expanded and, today, produces millions of dollars for most states and more than $4 billion for the federal government, more than quadruple the amount in 2001.

But there’s a growing problem with the practice.

Civil forfeiture happens outside of the normal criminal justice system, where such principles as the presumption of innocence, right to an attorney and others apply. In most states, there is no requirement that an individual be convicted of illegal activity before his or her assets are taken.

Police and prosecutors have taken advantage of this. In Michigan, which has some of the looser forfeiture laws, most forfeiture cases happen without a criminal conviction. And in about 1,000 cases in 2017, the most recent year for which data are available, someone lost their property without ever being charged with a crime or after charges were dropped.

We aren’t talking about major drug lords. The typical Michigan forfeiture case involved the seizure of about $200 in cash or a vehicle valued at less than $1,500 — more often than not from lower-income individuals. And because this happens in the civil court system, the person whose property was taken has no right to an attorney, meaning they’re on their own.

For decades, the Supreme Court has upheld the practice of civil asset forfeiture. But as the practice has expanded, the courts have begun to raise questions about its constitutionality. In 2017, in a case the court ultimately turned down, Justice Clarence Thomas, for example, launched a broadside regarding the “legal fiction” of charging property with illegal activity, rather than individuals.

More recent, in Timbs v. Indiana, the nation’s high court went further, ruling that forfeiture could be considered a type of fine and that states cannot violate the 8th Amendment’s prohibition of excessive fines.

In Timbs, an Indiana man was caught selling $225 worth of illicit drugs to undercover officers. He was convicted, sentenced to house arrest and probation, and fined $1,200.

Though the maximum fine he could have been required to pay was $10,000, police also seized his $42,000 Land Rover. If he had obtained this vehicle by profiting from selling illegal drugs, there would be no issue. But he didn’t: There was a clear record that he purchased it with money from his father’s life insurance policy.

Ruling that forfeiture of the Land Rover was a form of an excessive fine, the Supreme Court more firmly established that forfeiture cases involve mandated fines, which can be subject to statutory limitations.

In this instance, the case involved a person convicted of a crime. The threshold for what constitutes an excessive fine should be even lower for the thousands of people who are never convicted or even charged with a crime, but still have their money or property taken anyway.

If the Timbs decision encourages law enforcement officials to focus more of their efforts on securing criminal convictions before seizing people’s property, that would be a good thing.

Forfeiture is a necessary part of the law enforcement process. But it should be applied only after the accused have been convicted of illegal activity and the court finds they profited from it.

The Supreme Court has tipped its hat in this direction. The states should take notice and make sure that property rights are protected, even for those suspected of violating the law.

Editor’s note: Jarrett Skorup, author of the report “Civil Forfeiture in Michigan: A Review and Recommendations for Reform,” is the director of communications at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a research and educational institute in Midland, Michigan. He wrote this for InsideSources.com.

![0x0[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/0x01-scaled-1.jpg)

![105175361-GettyImages-170854342[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/105175361-GettyImages-1708543421.jpg)

![ICEpolice-2-1250×650[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ICEpolice-2-1250x6501-1.jpg)