The Continuing Perversity of Civil Asset Forfeiture

In too many places, law enforcement can still seize cash or property without proving a crime. States have begun to enact protections, but there’s more that policymakers can do to rein in policing for profit.

April 01, 2021 • American Conservative Union, David Safavian

Facebook

LinkedIn

Twitter

Email

Print

shutterstock_1865464819

(Shutterstock)

Law enforcement takes a particularly harsh view of folks who take money meant for public purposes and spend it on themselves. And rightfully so. But when money is from civil asset forfeiture, it seems it’s fair game.

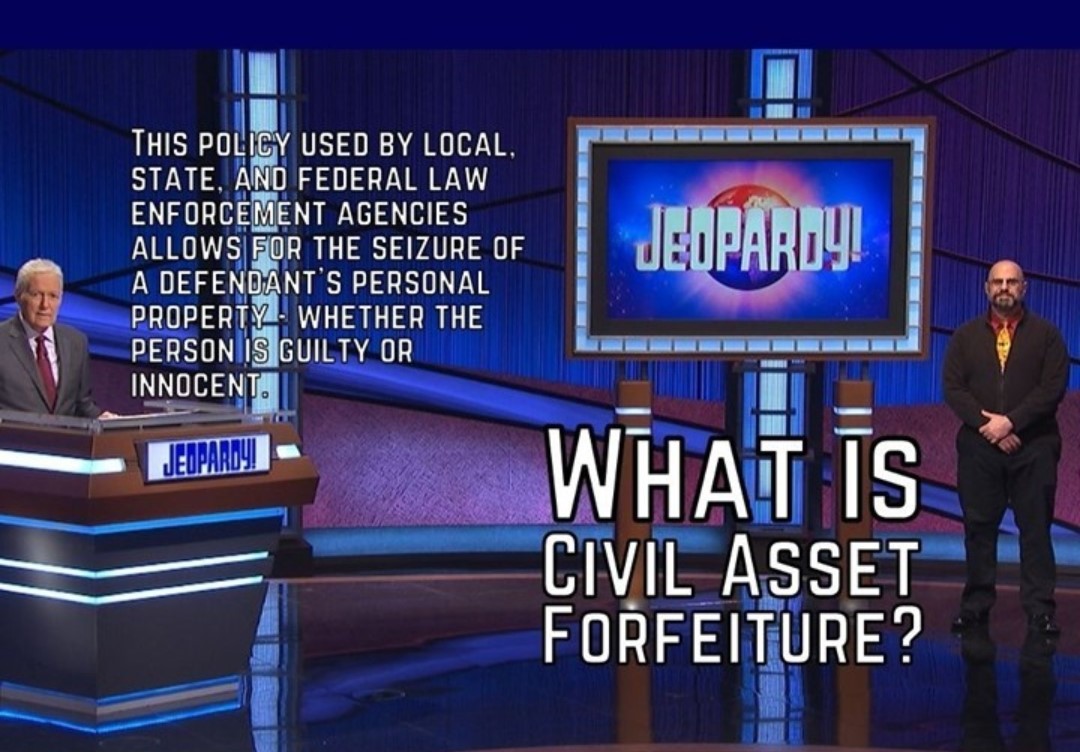

When most people hear about civil asset forfeiture, they are outraged. It is difficult to imagine that the government can take cash or property without having to prove any connection to criminal activity. But that is the case with this judicially created power granted to law enforcement. Civil forfeitures often occur without any judicial proof aside from vague assertions that assets are “likely” connected to criminal activity. In many states, prosecutors don’t even need to file criminal charges to seize cash, cars or homes. But the most perverse issue with civil forfeiture is that it turns the presumption of innocence on its head by requiring owners to somehow prove their property was not related to criminal activity. Because proving a negative is nearly impossible, most give up.

This system is rife with abuse. The Institute for Justice (IJ) has documented how police have seized cash from Christian bands, small business owners, professional poker players and church deacons, based on an officer’s “sense” that someone was carrying too much money. People carry cash for reasons that have nothing to do with drugs. Too often, poor and minority folks who disproportionately lack access to financial services are targeted. But under the Alice-in-Wonderland rules of civil forfeiture, legal conduct becomes proof of guilt.

The IJ report tallied nearly $69 billion in forfeiture revenue over two decades. Where does the money go? As the IJ has documented, 43 states allow police and prosecutors to keep half or more of the proceeds, which incentivizes seizures. Departments use forfeitures to pad budgets and buy goodies outside of the appropriations process. Rather than allowing legislators to balance law enforcement needs, civil forfeiture creates slush funds, often spent without accountability under the pretense of law enforcement needs.

Journalists following the money have discovered, for example, that state revenue investigators in Georgia used seized assets to purchase travel to junkets, engraved firearms, “gym equipment, commemorative Super Bowl badges, golf carts, $130 sunglasses — even stress balls shaped like beer mugs and wine bottles.” Police in Hunt County, Texas, paid themselves bonuses of up to $26,000 per year. And in one infamous case involving the elected prosecutor of Macomb County, Mich., — who was indicted in connection with the case — the goodies allegedly included $10,000 for purified water, $7,000 for parties and $8,000 for DirecTV.

Civil Forfeiture Law Grades

a+U.S.+map+displaying+each+states%27+grade+for+civil+forfeiture+law

Zoe Manzanetti

(Source: Institute for Justice)

With abuses making headlines, states have begun to enact increased forfeiture protections. At least 15 jurisdictions now require a criminal conviction before a civil forfeiture proceeding. Three have eliminated civil forfeiture altogether. Courts, following the example of the Supreme Court, have also begun to scrutinize seizures more closely.

Despite progress in fixing the system, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions worked to gut many reforms by authorizing so-called “adoptive seizures.” Here, a local police department otherwise limited in its asset forfeiture powers under state law turns the case over to the Justice Department. With nearly unbridled power, the federal government seizes the assets and kicks back as much as 80 percent as a finder’s fee. The allure is obvious: an end-run around state civil asset forfeiture reforms. In effect, the federal government is laundering the ill-gotten gains of law enforcement and taking a cut. If anyone other than the Justice Department laundered money in this way, criminal charges would result. Reversing the Sessions policy should be on the to-do list of the new attorney general, Merrick Garland.

But state policymakers must also scrutinize how law enforcement agencies are wielding asset forfeiture powers, where the money goes and what, if any, controls on spending exist. If policymakers have already put meaningful limits in place, they should ensure that those limits are not being circumvented by DOJ’s adoptive forfeiture program. Most importantly, by requiring forfeiture funds to go back into the general treasury and be obligated properly rather than going to an off-the-books slush fund, policymakers can remove incentives for abuse.

Some defend asset forfeiture as an important tool for law enforcement. But its overuse has strained the public’s bond with those on the thin blue line, thereby making their jobs more difficult and dangerous. It is time to rein in policing for profit.

![pfp_social[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/pfp_social1.jpg)

![20180903_d2c5ea2e-0888-57b3-b04a-ab689f32c70c_1[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/20180903_d2c5ea2e-0888-57b3-b04a-ab689f32c70c_11.jpg)