This Week’s Civil Forfeiture Outrage (Twelfth in a Series: Love Field Update)

A few months ago, I blogged about the curious case of a currency seizure at Dallas Love Field. In December, the Dallas Police Department (DPD) seized more than $100,000 in currency from a traveler journeying to Chicago, apparently after a drug-sniffing dog sensed the smell of marijuana from her suitcase. As I wrote then, there were lots of questions about this incident that journalists should be asking:

Why is the dog being praised—and what exactly did the dog accomplish? Why was this money taken from this woman? If the Dallas Police Department thought she was committing a crime, why wasn’t she arrested? If they didn’t think she was committing a crime, why was her money confiscated? When police confiscate cash on the theory that there’s been some kind of wrongdoing, do they need to have some kind of evidence of wrongdoing beyond the mere existence of the cash?

When I emailed a DPD spokesperson a few questions about this incident, I received a brief and cryptic email back. The spokesperson responded that “there is more to this story,” but that she couldn’t say anything else. Perhaps because of DPD’s stonewalling and innuendo, CBS Channel 21 then filed a records request to get more details. What they found, as far as I can tell, isn’t helpful to the police.

The documents released by DPD identify the woman that the cash was seized from and label her a “suspect”—even though she was never detained or charged with a crime. The DPD’s report describes its investigation, and it concludes that the money might be related to drug trafficking for the following reasons:

The dog alerted to drug odors; indeed, the detective who opened the bag reported “smelling the odor of marijuana.” There was no marijuana in the bag, though, just cash.

The “suspect” looked around when interviewed, and her statements were sometimes hesitant and inaccurate.

The report notes that when the woman was asked if she was carrying cocaine, methamphetamine, or heroin, she stated, “No.” But when she was asked about marijuana, police noted she hesitated and her eyes darted to the left when she again answered, “No.” Police then asked if she was carrying large sums of cash; again, she hesitated, her eyes darted to the left, and answered, “No.” The woman then said she had about $20,000 inside of the luggage along with clothing.

Furthermore, she inaccurately described the suitcase as gray (in fact, it was black) and the lock on the suitcase as moveable (in fact, it was attached to the suitcase).

(In fairness, these justifications are an improvement to the DPD’s original explanation for the seizure. When the money was originally seized, DPD announced that “travelers are not allowed to board a plane with more than $10,000 of cash without declaring it, even on domestic flights.” That claim is pure fiction.)

If, after reading the above, your reaction is that “something’s fishy about this woman carrying all this cash around,” I’m inclined to agree. But, as Reason’s Joe Lancaster noted, what these facts highlight is the distinct absence of a crime. Fishiness isn’t illegal. It isn’t illegal to carry cash. It isn’t illegal to possess a suitcase that smells of marijuana (possession of marijuana happens to be legal in the “suspect’s” destination, Illinois). It isn’t illegal to be nervous when interrogated by police, even if nervousness causes your eyes to dart around. It isn’t even illegal to inaccurately describe the personal property you’re carrying.

Of course, even if this woman’s choices weren’t illegal, they appear quite inadvisable. More precisely, actions like these can generate suspicion from law enforcement officers. That’s why concepts like “reasonable suspicion” and “probable cause” are so important in criminal justice— enough suspicious behavior allows law enforcement officers to detain and arrest people.

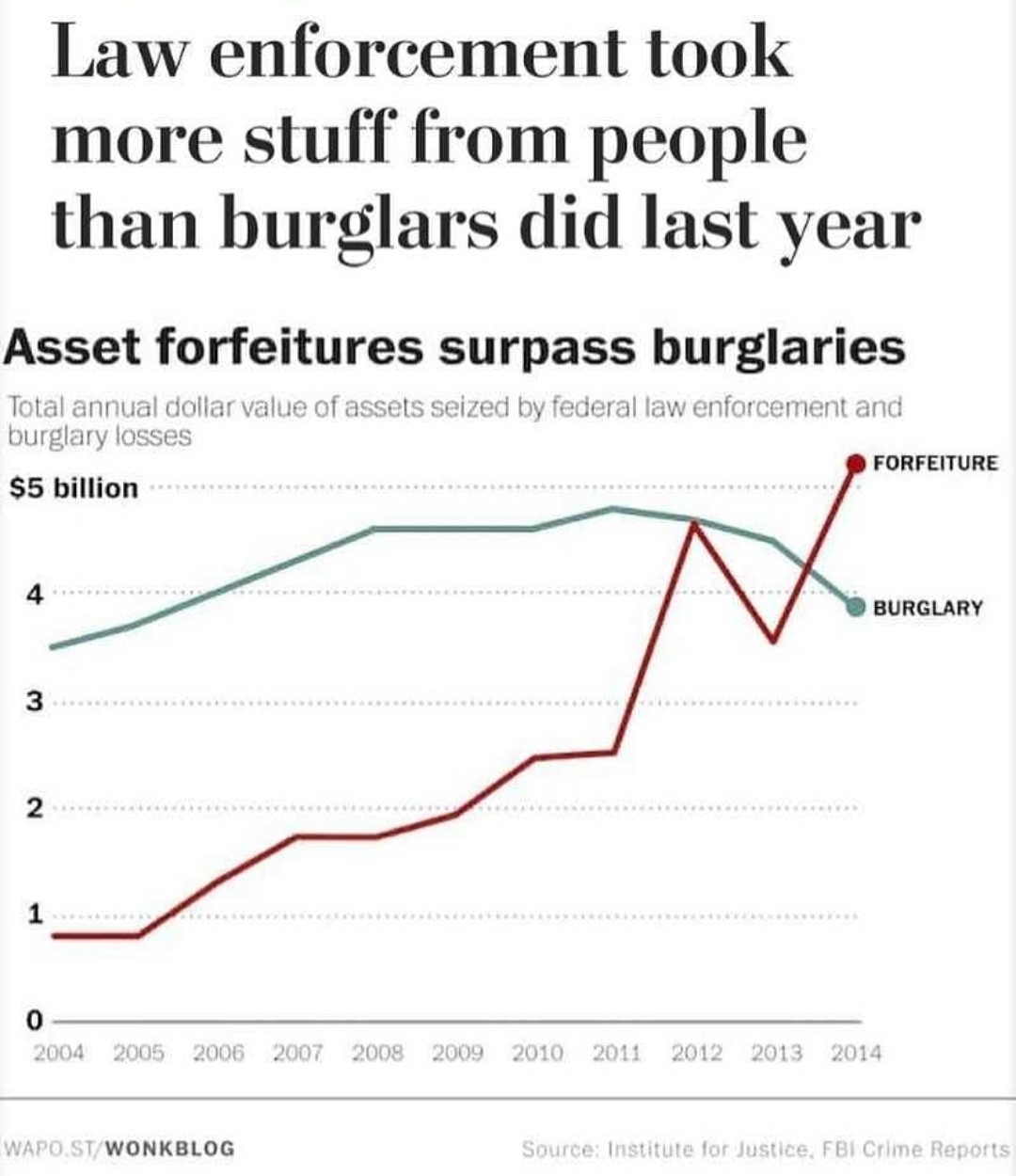

Any justice system has to have rules that determine the circumstances in which the cops are allowed to detain citizens. In the last few decades, we’ve imported the rules of civil asset seizure into the criminal justice system. But this blended civil and criminal system has produced outcomes where the alleged suspect is never arrested, never booked, never charged, and never tried. The seizure serves as the trial.: It’s often the only justice that a “suspect” is going to get.

That’s a general rule, even though it may not be true in the Love Field case. At some point, it’s certainly possible that a lawyer for the “suspect” will file suit in an attempt to get the $100,000 back. But in most cases, victims of seizure cannot and will not pursue the recovery of their own property. If a victim of civil asset seizure has lost, say, $1,000 in cash to the authorities, he or she is certainly entitled to consult with a lawyer. If the lawyer tells the victim that it’s going to cost $2,500 in legal fees to get the money back, the victim would have to be crazy to follow through with the lawsuit. That’s a central reason why about 80 percent of civil asset seizure cases are never litigated. Even though the victim has the formal right to show up in court and pursue recovery, it makes no sense for him or her to throw good money after bad by hiring a lawyer. In short, the victim of seizure typically has very good reason just to eat the loss.

Some aspects of the Dallas Love Field civil seizure are atypical. When currency is involved, the typical civil seizure involves a few hundred or a few thousand dollars. It’s atypical that someone would just walk away from $100,000 without trying to figure out how to get it back. What is typical about the Love Field seizure, though, is its injustice.

![GettyImages-859630296[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/GettyImages-8596302961.jpg)