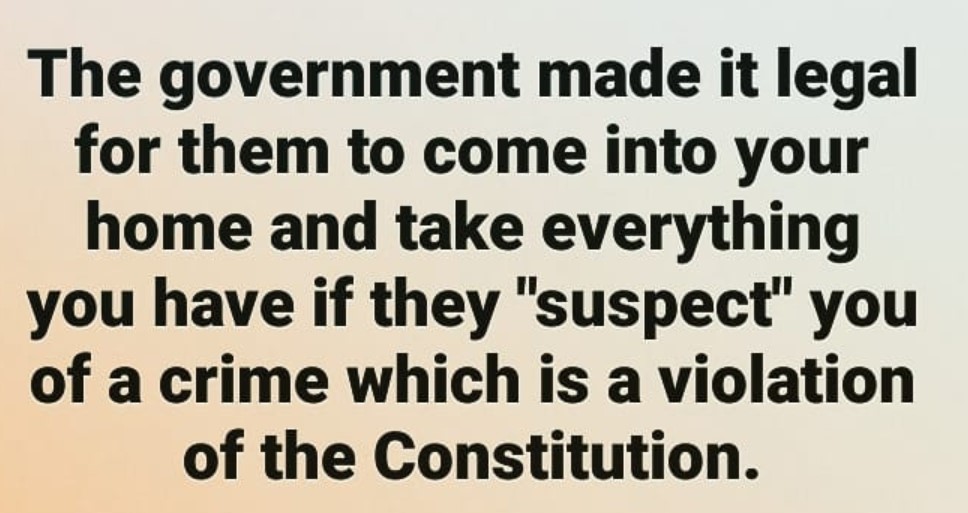

This Week’s Civil Forfeiture Outrages: Do People Facing Forfeiture Get Due Process?

A high-profile reversal of a recent civil forfeiture case makes me wonder: Do those who face civil forfeiture generally receive due process of law? That is, are those who face forfeiture being treated fairly? Some recent evidence provides grounds for skepticism.

The case in question involves Jerry Johnson, from whom police seized $39,500 in cash shortly after he arrived at Phoenix’s airport—even though Johnson was not and has never been charged with a crime. When the matter came to court, Johnson testified that he had received the money lawfully, through his business and a loan from his uncle, presenting evidence that included a receipt for cash withdrawal of roughly half the money in question. Johnson’s story was that he flew to Phoenix to buy a truck at auction for his business and that he thought that he’d get a better deal with a cash purchase.

The prosecutors told a different story. They claimed that Johnson’s credibility was shaky. Not only did Johnson allegedly fit the profile of a drug dealer, he didn’t know exactly how much in cash he was carrying. Furthermore, he equivocated about the source of the money—at the airport, he said his mother and sisters loaned him money; at trial, he said the source of his loan was his uncle. He also had already bought a return ticket to fly back to North Carolina, even though he told the court that he planned to buy the truck and drive it home. Furthermore, the auction house had announced on its website that it wouldn’t accept cash payments.

The trial court found that, due to discrepancies like these, Johnson’s testimony was “not believable.” That court concluded that it was more likely that Johnson was trafficking drug money than that he was just trying to buy a truck. Notably, the court simultaneously entertained testimony from the prosecution about two separate matters: whether there was probable cause to seize the money and whether Johnson was its true owner.

On appeal, a three-judge panel found that the trial court had improperly mixed the analysis of probable cause for seizure with the analysis of ownership. In effect, this forced Johnson to prove that his possession and ownership of the money was unconnected to criminal actions, because that mixture conflated evidence of probable cause for the forfeiture with evidence for Johnson’s ownership. Even though prosecutors argued that Johnson had failed to prove ownership, they never supplied information regarding a crucial question: If it is not Johnson’s money, then whose money is it? (At the oral argument on appeal, Judge Peter Swann, who would go on to write the decision overturning the trial court, perhaps tipped his hand when he asked prosecutors: “I don’t know how much I have in my wallet. Do you need to check it? Should I be worried that the police are going to come check it? Am I going to have to explain where I got it?”)

Ultimately, the appellate court reversed the judgment, sending the matter back to the trial court. Cheers for the lawyers from the Institute for Justice who represented Johnson!

This isn’t a one-off matter, though; courts regularly tell cops that their seizures are wrongful. Just the other day, I learned about a recent case involving a fellow named Rahkim Franklin, who wanted to purchase a cashier’s check from a bank for a down payment for a home. Unfortunately, his home loan was denied and he didn’t buy the check. He left the bank – still cash-rich, and shortly thereafter was pulled over by a sheriff’s deputy on the basis that his car windows were “overly tinted.”

One thing led to another. The deputy smelled “a strong odor of marijuana,” leading to a search of the car, leading to the discovery of the cash and a loaded handgun under the seat. Franklin was arrested on concealed weapons charges and the cash was seized. Ultimately, in the face of questioning by law enforcement authorities about the origin of the money, Franklin asserted his Fifth Amendment rights. Investigators ultimately determined that such factors as Franklin’s invocation of the Fifth Amendment, his lack of verifiable income, his past history of marijuana use, and his familial relationships with people in the drug trade supported seizure and forfeiture of the cash.

The prosecutors’ theory fell apart upon judicial examination. A court is not required to draw negative inferences in a civil case when a party invokes the Fifth Amendment. Smoking marijuana is not evidence of drug dealing. Having family members who commit illegal conduct is not evidence of personal criminality. Franklin had apparently relied on an old-fashioned living arrangement that sharply reduced his expenses: He lived with his grandmother. In his decision in the case (United States v. Approximately $13, 205.54 in U.S. Currency), District Judge Martin Reidinger noted:

For the Government to suggest that a citizen’s mere possession of firearms implicates that person in illicit drug trafficking is to strain credulity. The Government’s argument presents some Second Amendment considerations that counsel has apparently not considered.

At this point, perhaps the reader is reacting by saying: We know that cops sometimes make errors. When that happens, courts correct them, because that is what courts are supposed to do. What is the problem?

The problem is that civil seizure and forfeiture are different, because these situations rarely make it into court. As I have written previously, a typical cash seizure and forfeiture can range from several hundred dollars to a bit over $1,000. The cost of pursuing recovery in such cases can be prohibitive. It just isn’t worth the time or money it would take to get your currency back, so the victim in such cases must eat the loss.

Cases like Franklin’s or Johnson’s, in which the owner manages to get legal representation in order to recover the property, are the exception. Around 80 percent of forfeiture cases end in default judgment. The victim of seizure never shows up in court to plead his or her case. That means that, for the typical roadside stop that leads to forfeiture, the justice you get from the policeman on the street is all the justice you’re going to get, period. Those who don’t go into court aren’t going to get any justice from the court. That is one serious absence of due process of law.

![102530953-RTR4TL5M[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/102530953-RTR4TL5M1.jpg)

![107091439-1658324524435-gettyimages-622164342-AFP_HZ910[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/107091439-1658324524435-gettyimages-622164342-AFP_HZ9101.jpg)

![pfp_social[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/pfp_social1.jpg)

![veteran-benefits-in-Oregon[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/veteran-benefits-in-Oregon1.jpg)