Our View: Civil asset forfeiture, meant to fight crime by taking profits from drug dealers, often turns cops into bounty hunters who can’t imagine the many legitimate reasons people carry cash.

The Editorial BoardUSA TODAY

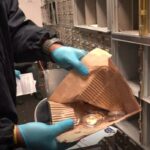

The majority of asset forfeiture seizures is cash.

Terry Rolin, like his Depression-era parents, shunned banks and kept his life savings of more than $82,000 hidden at his suburban Pittsburgh home. What Rolin didn’t realize was that he had more to fear from law enforcement than from banks.

When Rolin, a retired railroad worker, moved to an apartment, he decided to entrust the money to his daughter, Rebecca Brown, to open a joint bank account in Boston, near her home.

But as she was set to fly home from Pittsburgh International Airport, the Transportation Security Administration spotted the cash in her carry-on and called authorities. A Drug Enforcement Administration agent questioned her, didn’t believe her answers and seized the money under a program that was created to target illegal proceeds from crimes.

No swindlers and drug dealers

The agent had no reason to suspect Brown of any crime, and neither she nor her father were ever charged with one. Yet it took these innocent citizens more than six months, with help from pro bono lawyers and a class action lawsuit against the government, to get their money back last year.

At least their nightmare ended happily – far better than for tens of thousands of innocent people whose cash, cars or even homes are seized and permanently kept by local, state or federal law enforcement under “civil asset forfeiture.”

USA TODAY’s opinion newsletter:Get the best insights and analysis delivered to your inbox

Forfeiture is meant to battle crime by taking profits from swindlers and drug dealers, and at times it does. But the way it has been used for decades, it too often ensnares law-abiding citizens.

Why?

Cash-strapped agencies

One reason is that federal, state and local authorities get to keep all or part of the forfeitures they take in. Since 2000, they’ve taken in nearly $69 billion, according to a report by the Institute for Justice, a libertarian legal group that has sued the government in forfeiture cases. That’s 69 billion reasons for cash-strapped agencies to grab money, whether or not it’s justified.

And it’s so easy.

Police need only to suspect your property is somehow involved in a crime. They don’t have to charge you, let alone convict you of anything. And once they seize something, it’s up to you to prove in a complex and expensive system that it is not derived from a crime. Basically, you’re guilty until proven innocent.

Fix qualified immunity travesty that lets police off the hook

Limiting no-knock warrants is not enough. The Breonna Taylor tragedy leaves no doubt.

Police should avoid minor traffic stops that too often turn tragic

Police who violate Bill of Rights don’t deserve protection

Why are innocent people still losing cash, cars and even homes to police?

Young Black men shouldn’t have to endure unwarranted traffic stops as a rite of passage

Like so much else in today’s criminal justice system, the brunt of forfeiture falls on those who can least afford to fight back. The majority of seizures are cash. Across 21 states with available data 2015-19, the average forfeiture was $1,276 – not exactly drug lord fortunes.

Because many low-income and minority people don’t have bank accounts, they use cash and become easy prey for law enforcement. Once their cash is confiscated, they often have no money to hire a lawyer and are forced to let the money go.

Legitimate reasons people carry cash

Civil asset forfeiture turns authorities into bounty hunters who somehow can’t imagine the many legitimate reasons people carry cash. They’ve snatched large amounts of cash from people carrying it to buy a used car, to close a business deal or simply because it’s the proceeds of their legitimate cash business.

A deputy in rural Muskogee, Oklahoma, stopped a driver on the highway for a broken taillight and seized $53,000 in donations collected from charity concerts for a Christian college in Myanmar and a Thai orphanage. Only after horrendous national publicity and intervention by an Institute for Justice lawyer did the government return the money.

Reform in New Mexico, Maine

Three dozen states have passed laws since 2014 to rein in the system’s abuses. But a huge loophole often remains: To get around state law, local police can partner with federal law enforcement in a forfeiture case and get up to 80% back as a kind of finder’s fee.

New Mexico, in a 2015 law, found a way to get around this problem. The state not only requires a conviction before taking money or property permanently, it also mandates that all proceeds go into the state’s general treasury rather than directly to police. And it has cut into the ability of police to partner with the feds.

In Maine, a new measure that abolished civil asset forfeiture became law this week.

Other states should take note. And if Congress is serious about police reform, it should eliminate federal agencies’ outrageous use of civil forfeiture and end the program that allows sharing with states.

Forfeiture is one more reason many law-abiding citizens fear and distrust law enforcement. In America, no one like Terry Rolin or his daughter should have to battle the government to get back their hard-earned property.

In the wake of a police officer’s conviction for murder in the killing of George Floyd, USA TODAY Opinion is producing a series of editorials examining ways to reform police departments across the USA.