Yes, police in most states can seize your money even if you’re not charged with a crime

Through a process called civil forfeiture, the government can seize your money if they believe it is linked to a crime.

Some Google search ads can be used by scammers to redirect to scam sites

No, the federal minimum wage is not scheduled to increase in 2024

Author: Nate Hanson, Brandon Lewis

Published: 8:34 PM EST December 8, 2021

Updated: 5:32 PM EST December 9, 2021

Facebook

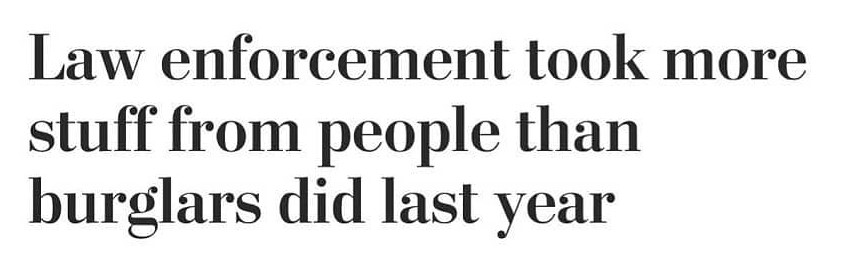

On Dec. 7, 2021, a Dallas, Texas, television station published a story about a K-9 officer that helped police seize a bag with more than $100,000 at the Love Field Airport. The station’s tweet about the story was shared more than 5,000 times and led to some people questioning why the money was seized.

Readers noted that the story pointed out the person who owned the bag was not arrested. One person responded, “Is it illegal to have money?” Another person, whose response was retweeted more than 6,000 times, said that police can seize people’s money even if they are not charged with a crime.

THE QUESTION

Can police in most states seize your money even if you’re not charged with a crime?

THE SOURCES

Laws from Maine, Nebraska, New Mexico and North Carolina

U.S. Department of Justice

Institute for Justice

Texas Appleseed

THE ANSWER

This is true.

Yes, police in most states can seize your money even if you’re not charged with a crime.

Through a process called civil forfeiture, the government can seize your money if they believe it is linked with a crime. To get the money back, owners often must show they are unaware of the illegal conduct or did all they could to stop the illegal activity.

WHAT WE FOUND

The practice of seizing and keeping property suspected of being used in criminal activity is known as asset forfeiture

“Asset forfeiture is designed to deprive criminals of the proceeds of their crimes, to break the financial backbone of organized criminal syndicates and drug cartels, and to recover property that may be used to compensate victims and deter crime,” the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) says.

There are three types of asset forfeiture: criminal, civil and administrative. The story about more than $100,000 being seized at a Dallas airport is an example of the civil forfeiture process, which is what we’ll focus on.

Most states and the federal government have civil forfeiture laws.

In a civil forfeiture case, the government brings action against the property, meaning the defendant in the case is the property itself and criminal charges don’t have to be filed against the owner, according to the DOJ. If challenged, the government, as a basis for forfeiture, must then show in court that there is a connection between the property and illegal activity. To get their property back, owners often must show they were unaware of the illegal conduct or did all they could to stop the illegal activity.

The government says civil forfeiture helps impede criminal activity. Critics argue civil forfeiture limits the due process rights of property owners because they don’t have to be involved in a crime to lose their property.

The Institute for Justice, a nonprofit that advocates for the end of civil forfeiture, says four states have abolished civil forfeiture and use criminal law to forfeit property. Those states are North Carolina, New Mexico, Nebraska and Maine.

Several other states require a criminal conviction before beginning civil forfeiture proceedings, but Texas, where the seizure of more than $100,000 took place, does not.

Dallas police claimed in a report that the money seized at the airport was part of a drug trafficking investigation, even though the traveler wasn’t arrested.

While there is a process in Texas to get the money back, Texas Appleseed, which works on criminal justice reform, says defenses are usually expensive and a majority of cases go uncontested.

States can also work with the federal government on civil forfeiture cases through a federal program called equitable sharing. The partnership allows local and state law enforcement agencies to transfer seized property to the federal government for federal forfeiture. The state or local agency could then get some of the net proceeds of the forfeiture.

The DOJ says the program provides additional resources and strengthens cooperation between federal, state and local law enforcement agencies. Opponents argue equitable sharing gives law enforcement a financial stake in seizures.

The type of seized assets that can be transferred to the federal government is dependent on state law. The Institute for Justice says eight states and the District of Columbia have passed laws to limit equitable sharing. For example, Maine only allows equitable sharing in cases when more than $100,000 in cash is seized.

![20180903_d2c5ea2e-0888-57b3-b04a-ab689f32c70c_1[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/20180903_d2c5ea2e-0888-57b3-b04a-ab689f32c70c_11.jpg)

![PrivateProperty3-1250×650[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/PrivateProperty3-1250x6501-1.jpg)

![0x0[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/0x01-1-scaled-1.jpg)

![bank-banking-banknotes-blur-thumbnail[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/bank-banking-banknotes-blur-thumbnail1.jpg)

![Font-NPR-Logo[1]](https://rucci.law/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Font-NPR-Logo1.jpg)